The Kyiv Independent: Upcoming elections can change where Turkey stands on Russia’s war

tr-ukraine-russia-map

tr-ukraine-russia-map

As Turkey reels from an economic crisis and a devastating earthquake, its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, faces the most nail-biting election since his Justice and Development Party (AKP) took power two decades ago.

Erdogan has managed to hold on to power since he became the prime minister in 2003, moving into the president's office in 2014.

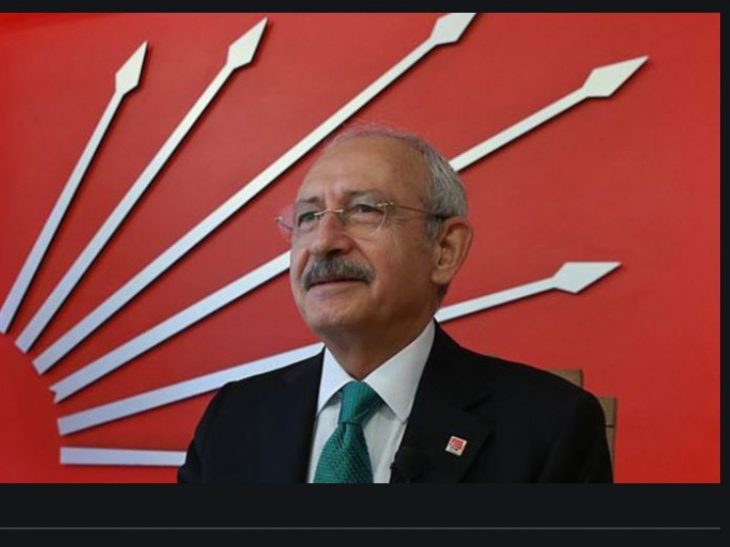

But now, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the joint candidate of the opposition, is leading in the polls ahead of the May 14 general elections. AKP is looking weaker in polls as well.

A change in leadership could affect Russia's invasion of Ukraine, experts said.

Turkey has been a major diplomatic intermediary between the two warring countries, with Erdogan often getting personally involved. If he's ousted, Turkey may become closer to the West but also become a less active negotiator.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6ULaXA7P24[/embed]

"Erdogan enjoys very close ties with Putin. It allows him to broker deals between Russia and Ukraine," Berk Esen, assistant professor of the Sabanci University in Istanbul, told the Kyiv Independent. But Esen also played down Turkish diplomacy, saying Russia agrees to deals when it wants something.

The current Turkish government is trying to balance Ukrainian and Russian demands. Turkey supplies Ukraine with attack drones and has closed off the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits to warships from any country, including Russia.

On the other hand, Turkey is negotiating to become a Russian gas hub and has released Russian vessels carrying stolen Ukrainian grain. Turkish companies have reportedly helped Moscow dodge Western sanctions.

Erdogan's government has also played an intermediary in large prisoner-of-war exchanges between Ukraine and Russia and is directly involved in the grain deal.

But despite Turkey's growing role in the region, foreign policy is not a key priority for its society. Voters care mostly about the economy, according to opinion polls.

"If the opposition wins, Turkey is not going to play a high-profile role in negotiations between the countries," Esen said.

The Race

Erdogan became Turkey's first executive president in 2018 following a controversial constitutional change that allowed him to impose a state of emergency, appoint top officials and intervene in the legal system.

Soon, the popular Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, who intended to run against Erdogan, received criminal charges in 2022. Those opposing Erdogan later united around Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, leader of the Republican People's Party (CHP), the country's main opposition party.

Kılıçdaroğlu has led the "forever runner-up" Republican People's Party (CHP) since 2010. At that time, this main opposition party lost four parliamentary elections to Erdogan's AKP.

But in recent years, Erdogan's run of popularity seemed to have petered out. He has been at least partially blamed for Turkey's economic crisis that began in 2018.

Erdogan's popularity rebounded over the past year, thanks to his cash bonuses to state employees and the opposition movement's indecisiveness on running a joint candidate.

But the devastating earthquake that hit Turkey in February, killing over 50,000 people and causing over $100 billion in economic damage, put the brakes on Erdogan's comeback. The disaster affected regions home to 15% of Turkey's voters.

Yevgeniya Gaber, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Turkey, said that "the earthquake altered electoral trends, as any such challenges are the primary test of power."

Polling in Turkey can be a hazy business, but March polls suggest that Kilicdaroglu is ahead of Erdogan by over seven percentage points and polling just north of 50%.

The parliament elections are also favoring the opposition. The National Alliance, consisting of CHP, Good Party, and their allies, is looking to beat Erdogan's Justice and Development Party and the Nationalist Movement Party, supporting the current president.

The left-wing People's Democratic Party, which endorsed Kılıçdaroğlu, is also polling at over 10%.

"The earthquake boosted the opposition ratings," Gaber, a diplomat and former foreign policy advisor to Ukraine's prime minister, told the Kyiv Independent.

A darth of diplomats

Erdogan, accused of having a strong-arm approach, has held the reins of Turkey's foreign policy. The opposition has promised to return to a parliamentary republic, where the foreign ministry is run by diplomats, not the president.

However, while the opposition was able to assemble a stellar team of economists, the lack of experienced diplomats hurts their foreign policy program, experts said.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=doYJMK5Pilg&t=471s[/embed]

Two of the Nation Alliance's six constituent parties are headed by former foreign ministers – Gelecek Party's Ahmet Davutoglu and Democracy and Progress Party's Ali Babacan.

But neither is popular enough to have a good chance of becoming the next foreign minister, believes Hurcan Asli Aksoy, a Turkey Studies expert with the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

"It will be not wise to give an important ministry to one of them," Aksoy told the Kyiv Independent.

Somebody from CHP has the best chance to take over the foreign ministry, but not many party members have a background in diplomacy.

Balancing act

Currently, Erdogan maintains a middle way, neither alienating Kyiv nor Moscow.

Gaber believes that if Erdogan is reelected, he will tone down his anti-Western rhetoric but continue to try to extract benefits from Russia.

"He might try to get more benefits out of a weakened Russia. From energy prices and cooperation on oil and gas to the Syria policy and other regional conflicts where Turkey has opposing interests with Russia," Gaber said.

According to experts, Putin's preference for Erdogan over potential newcomers is rooted in their longstanding relationship and Turkey's contribution to complicating the internal affairs of NATO.

By maintaining close ties with Erdogan, Putin avoids the challenges that could arise from dealing with unfamiliar faces.

Meanwhile, Esen believes an Erdogan victory will lead to "more or less the same balancing act, but slightly more pro-Russian."

On the other hand, Kılıçdaroğlu's foreign policy stance is uncharted territory, as he is focused on domestic issues.

"He has a rather more traditional sort of Kemalist foreign policy view, which is 'let's get back to the negotiation table and resume accession talks with the European Union.' He's been very silent on the U.S. and Russia," Esen said.

"Kılıçdaroğlu is not an expert on diplomatic issues," Esen added. "He hasn't really been very vocal, which is why I don't think that they would be significant ruptures in the opposition's foreign policy when it comes to Russia. I don't think that they can really strongly confront Putin."

Aksoy said that some policies, such as the "founding agreements of Turkish foreign policy," will not change, regardless of who wins. These include the 1936 Montreux Convention, which regulates maritime traffic through the Turkish Straits.

In other words, regardless of the election outcome, Turkey is unlikely to allow Russian warships to enter the Black Sea to threaten Ukraine with missiles.

Experts believe an opposition victory would make Turkey more pro-Western in principle but less hands-on with its diplomacy.

"If the opposition wins, it would recalibrate the foreign policy more headed in the pro-Western direction," Esen said, adding that the opposition victory "may benefit the Ukrainian side."

However, Gaber said that it would be "difficult to move away" from Erdogan's balancing act and take a strong stance in support of Ukraine.

Both major opposition parties, CHP and Good Party, support Ukraine and advocate rapprochement with the EU and NATO. They also say that Turkey should reduce its economic and energy dependence on Russia.

Yet, neither party wants to join sanctions against Russia, Gaber said. Both are in favor of maintaining just enough relations with Moscow to avoid the aversion of Western partners.

"The Good Party is much more focused on issues of Turkic peoples, the Crimean Tatars in particular. And it takes a tougher stance on the condemnation of Russian aggression in Ukraine in Georgia," Gaber said.

She believes that if the opposition wins, Turkey would keep up a calculated show of support for a pro-Western and pro-Ukrainian course while attempting not to irritate Russia.

"It seems we would have Turkey in the format of Olaf Scholz's Germany. It would be pro-Ukrainian, but very cautious, trying as much as possible to avoid making any harsh statements toward Russia for concern of escalation," Gaber said.

Excerpt only_____________________________________________________

Note from the author: Hello dear reader! It’s Alexander Khrebet. Thank you for taking the time to read this article.

We need your support to continue reporting on the key events in the region, like these elections. Your support is vital to keep the Kyiv Independent running. If you appreciate our work and would like to support us, please consider becoming our patron.

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/