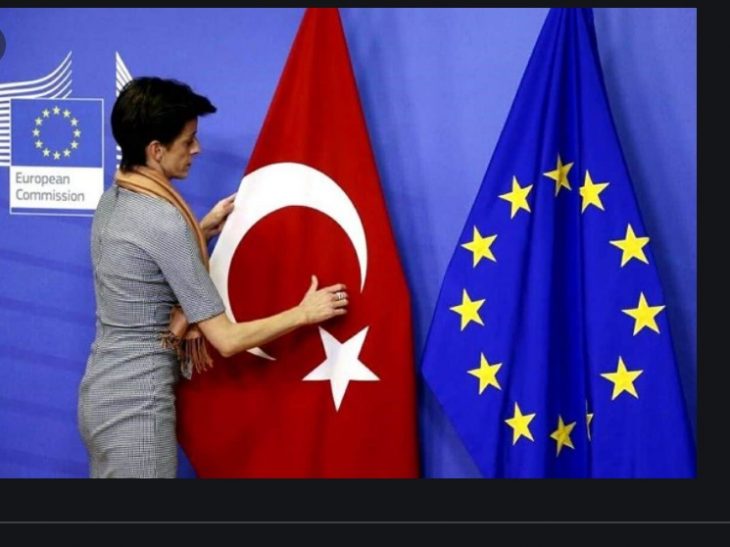

Bahadir Kaynak: How to unlock Turkish integration to EU?

Since the Turkish accession to EU stalled over the past decade or more, Turks have all but given up on this dream, while Europeans perceive Turkey either as a buffer zone keeping refugees out of Europe, or as a holiday destination. Bahadir Kaynak writing from Worldcrunch voices a novel solution advanced by Nacho Sánchez, Spanish politician and rapporteur for the European Parliament amy be the key to unlock the stalemate.

Geography is a real thing, and nothing changes the fact that Turkey is a large country attached to Europe, not only physically but economically and politically, too, argues Kaynak.

A draft report on this long-discussed problem, produced by Nacho Sánchez, Spanish politician and rapporteur for the European Parliament, was delayed due to the Turkish elections. The report is an effort to come up with a creative solution, and aims to offer an alternative to the EU accession process, which seems to have been on the ice for quite some time.

Both sides have legitimate complaints.

Ankara says the EU is discriminating against Turkey, and that the government sees no light at the end of the tunnel, despite waiting 60 years for membership. Even countries which were a part of the Eastern Bloc when Turkey and Europe signed the Ankara Agreement in 1963 have been members of the EU for nearly a quarter of a century now. Turkey, on the other hand, is trying to make do with a Customs Union treaty, which we cannot update, no matter what. All the while, the EU moves increasingly further away in the minds of average Turkish citizens.

Frozen accession

When it comes to the EU’s criticisms of Turkey, the anti-democratic practices that have become more intense in recent years are at the top of the list. Turkey’s stance on Cyprus, which both it and Greece claim, is another important agenda item.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv3c8a1dt4&t=24s[/embed]

In fact, the decline in democracy is more of a real problem for Turkish citizens than for the EU. It would be perhaps more appropriate to criticize the EU for contributing to the authoritarianization of the country by excluding Turkey.

On the other hand, if we look at the situation in some other EU member countries, we can also say that membership does not guarantee democratic policies.

Full membership is an earned right via international treaties

The process is gridlocked, no matter how right either side may be. European Parliament Rapporteur Sanchez suggests a creative solution, based on acknowledging that fact. But this is not a new subject: in Europe, some have long argued that full Turkish membership is not a realistic goal, and instead a vaguely defined “privileged partnership” status would be more fitting. Such theses became more common when former French President Nicolas Sarkozy came into power, but it's fair to assume that Germany tacitly approves of this approach as well.

There may not be any other perspectives left to support Turkey since the UK, which was the country's most vocal supporter, took itself out of the equation via Brexit.

But from the beginning, the Turkish government has strongly opposed the privileged partnership theory, arguing instead that full membership is an earned right via international treaties.

A step backwards?

Beyond that, there is also the idea that the accession process was as important as entering the EU itself. Ankara would gain momentum on important matters such as the rule of the law, democratization and a properly running market economy, as long as they remain true to the EU perspective.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFNuy8Hm2wE&t=31s[/embed]

But today, we can see that this opinion was not correct. One could argue that Ankara fell behind because they lost the EU perspective — regardless, going back to the way things were before is not possible. Even if Turkey does take steps toward democratization and a properly running economy, it wouldn’t be convincing to take that path just to satisfy Europe.

The refugee issue is becoming the main topic for European voters, and it seems hard to convince the public to support any increase in the asylum system while a recession looms and security fears fuel hostility towards foreigners. This is visible even in Germany, which has been relatively resistant to this concept, where right-wing populist party AfD is on the rise. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, known for being friendly to the Turkish government, was happy about the election results in Turkey, saying that he was glad that Turkey would remain a buffer zone between Europe and refugees. Even politicians who seem to be closer to Ankara don’t want Turkey in the EU, but value the country as a barrier which protects them from the masses at their door.

Obviously, the value of Turkey is not limited to the refugee issue. It is impossible to discard Turkey totally, because it is so integrated into the European economy, and because of its geopolitical importance — which became even more visible due to the war in Ukraine. Turkey’s stability is directly related to Europe’s own safety. Add Emmanuel Macron’s recently voiced dream of Europe being an independent political actor to all of these, and we can see that excluding Turkey completely wouldn’t be a rational move. The EU has temporarily burned bridges with Russia because of the war; it would be too costly to turn its back to Turkey.

The lack of a solid framework

Sanchez, the European Parliament Rapporteur, argues for an alternative mechanism, based on all of these facts.

On one hand, there is a need to prepare a framework for countries that aren’t EU members but are integrated into the continent, like Ukraine or the UK. Of course, there is also the fact that countries which are not involved in the decision-making processes of the EU may be reluctant to harmonize with its policies, and would instead rather take care of their own.

On the other hand, politics is the art of doing what’s possible. Creative solutions are required if the EU expansion process has ended for the foreseeable future, but the need for harmony between the sides remains. As Sanchez says, if the paused membership process blocks potential cooperation opportunities between the EU and Turkey, those obstacles should be eliminated. Maybe the process is not as important as membership itself. On the contrary, it’s a part of the gridlock.

Of course, it’s still too early to be optimistic, given the lack of a solid framework. Turkey's practical demands have yet to be answered, including issues around the Customs Union and the increased rejection rates Turkish citizens have faced when applying for Schengen visas. If a mechanism could be found to satisfy both the expectations of Turkey from the EU and Turkey’s agenda for democratization, political and economic reform, that would be a major development. Otherwise, we seem to be continuing on the path in which cooperation opportunities between the sides are wasted, and we remain stuck with a low-quality democracy and Turkish-style economics, just as it has been for the past 20 years.

Excerpt, Source: Erdogan III & Europe: Is There Any Future For Turkey In The EU?

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/