Turkey and Iraq: Two neighbors, too many problems

hakan fidan iraqi for minister

hakan fidan iraqi for minister

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is piling up the pressure on Iraq even as he enters a new era of reaching out to the country’s neighbors. Salah Nasrawi writing for al Ahram provides a comprehensive analysis of Turkey-Iraq frictions, which show no signs of abating.

In his article, Nasrawi states:

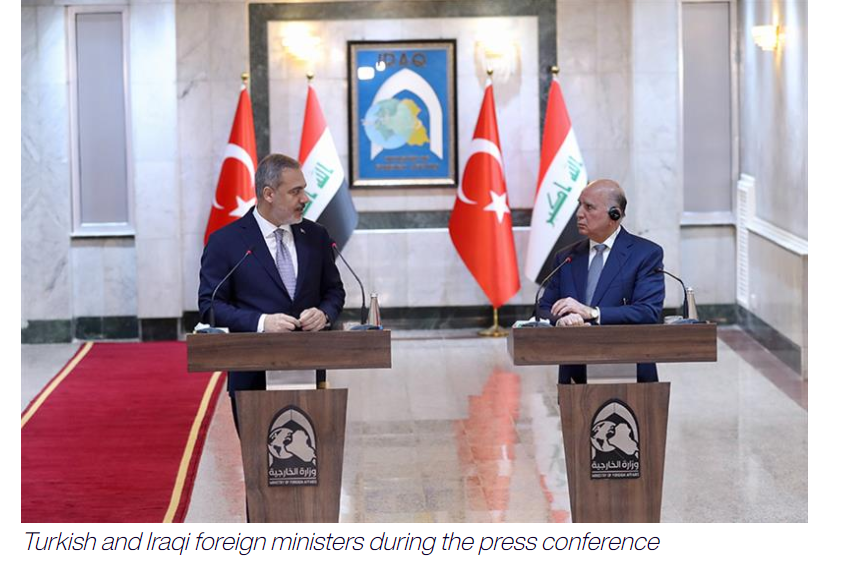

When Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan paid a visit to Iraq last month, expectations were high for a breakthrough in bilateral relations that had remained toxic over a host of political, energy, and security issues at the heart of their relationship.

But after three days of talks with numerous Iraqi political leaders along the political and ethnic spectrum, there were no signs that Fidan had managed to place relations on a new trajectory away from these thorny issues.

Fidan’s discussions with officials in the Iraqi Federal Government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Autonomous Authority in Erbil underlined important disagreements in priorities and goals between Iraq and Turkey.

In many respects, the failure of Fidan, one of the few confidants of Erdogan, in his delicate diplomatic mission has been underlining anxieties about the future of Iraqi-Turkish relations and Ankara’s real aims in its war-torn southern neighbour.

Iraq and Turkey have locked horns on several vexing issues, primarily Turkey’s refusal to reopen a pipeline that runs from Iraq’s Kurdistan Region to the Turkish port of Ceyhan, the severe shortage of water supplies from Turkey, and Turkey’s assertiveness in fighting Turkish-Kurdish guerrillas hiding in northern Iraq.

Turkey stopped the flow of Kurdish oil through the Iraq-Turkey pipeline after the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) ruled on 23 March in favour of Baghdad and against Ankara, saying that the latter had breached a 1973 agreement and allowed the Kurdistan Region to begin independent oil exports in 2014.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EIOH5A3WmM8&t=785s[/embed]

The Paris arbitration court ordered Ankara to pay about $1.5 billion in damages to Iraq for transporting oil without Baghdad’s approval. The suspension of the twin pipelines left millions of barrels of oil stuck in the Turkish port with mounting impacts on Iraq’s economy and Baghdad-Erbil relations.

During his visit last month, Fidan did not publicly acknowledge the oil blockade, but media reports suggested that Ankara has set some preconditions for resuming the exports through the pipeline, which carries Iraq’s 450,000 barrels per day (bpd) of exports to the Mediterranean.

While Ankara shows no intention of paying the fine, it wants the Kurdistan Regional Government to pay it to Baghdad as it is the benefactor of the exports. It has also made new demands for resuming the operation, including a new revenue-sharing deal.

Another critical issue that has served as a key obstacle to developing better bilateral ties is water flow from the Turkish highlands towards Iraq, as shortages of supplies have combined with climate change to severely impact the country’s central and southern provinces.

Water levels downstream in the two Rivers have been falling short in recent years, sparking fears of a potential threat to this lifeline upon which Iraq depends. Millions of Iraqis who rely upon these two great rivers to provide drinking water, agricultural irrigation, power generation and transportation have been badly affected after Turkey began filling the dams.

Turkey has intensified its cross-border incursions into northern Iraq in recent months, claiming its army is pursuing members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) whom Ankara accuses of using Kurdistan as a base for attacks against Turkey.

Over the last few weeks, Turkey has regularly carried out air strikes and drone attacks in northern Iraq, hitting targets deep inside the country and sometimes killing civilians.

While in Iraq last month, Fidan repeated the Turkish demand to both Baghdad and the Kurdish authorities to designate the PKK as a terrorist organisation and take action to end the group’s growing presence on Iraqi territory, which Turkey views as a threat to its security.

However, despite the strains in the relationship, the two countries still have much in common, including trade, investment, and tourism.

According to the UN COMTRADE database on international trade, Turkish exports to Iraq amounted to $13.75 billion in 2022, making it the second-largest trading partner with Iraq after China.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oSO4ZC-DSh4&t=38s[/embed]

Turkish firms from the energy extraction, commerce, and construction sectors are also investing and expanding in Iraq in projects involving infrastructure, hospitals, schools, and public buildings.

Turkey is a favourite destination for Iraqi tourists, and over 600,000 Iraqis flocked to Turkey during the first seven months of this year, according to the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, making Iraq one of the leading Arab countries in terms of the number of tourists to Turkey.

In addition, Iraqis have been among the top property buyers in Turkey, purchasing some 50,000 houses in past decades and adding investments in real-estate business and therefore prosperity to Turkey’s ailing economy.

Iraqi-Turkish economic engagements could have been advantageous to both neighbours, while cementing political ties. Yet, Iraqi-Turkish relations are not a vibrant, two-way dynamic in which both sides would be able to achieve sustainable and win-win deals.

A closer look into the Iraqi-Turkish relationship reveals an exploitative, assertive, and even neo-colonial approach that focuses on getting the most out of these relations through Turkey’s attempts to use its power to achieve its goals.

Turkey’s logic in its Iraqi policy is simple: weaponising water and energy exports against a slumbering Iraq in order to increase the pressure on Iraqi decision-makers who are too weak to stand up to Erdogan’s agenda.

This strategy of taking advantage of the weakness of the Iraqi state and its domestic fragility emanating from its poor leadership, political uncertainty, security instability, and the divergent interests of its various ethnic and religious groups creates space for foreign actors to play out proxy battles in the country.

Turkey has been building its case regarding security concerns arising from the PKK’s threats to its southern border, but by driving the party’s fighters, and indeed the whole Kurdish issue in Turkey into Iraq, it is creating a conflict zone in its own backyard.

Turkey cannot ignore the root causes of its Kurdish challenge and try to dump it on Iraq. This policy will not only cause further problems inside Turkey because it misses the underlying causes of the Kurdish question, but it will also exacerbate Iraqi and regional instability with adverse impacts on Turkey itself.

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel