Kurdish dilemma in Turkey’s foreign policy as Erdoğan tries reconnecting with Esad

Syria turkey

Syria turkey

For the foreseeable future, we can assume that the stance on the Kurdish issue will continue to play a decisive role in domestic and foreign politics as long as the Erdoğan administration needs the support of the nationalist front it clings to in order to reproduce its power.

Can Cemgil * -Artı Gerçek

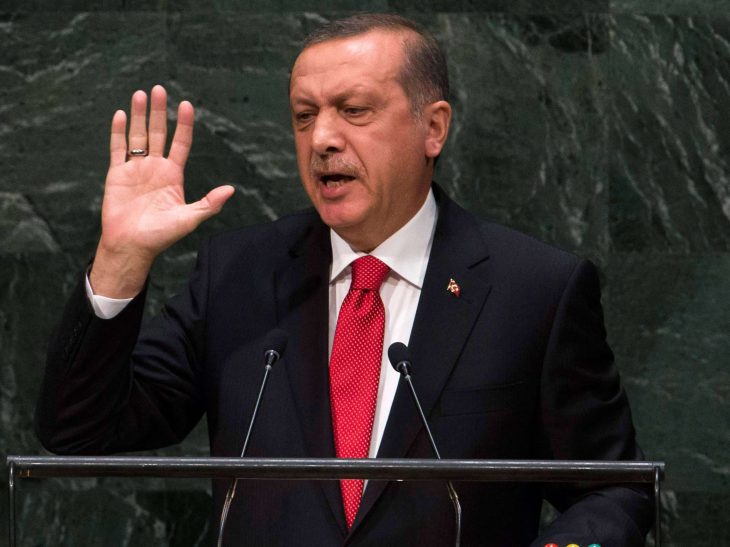

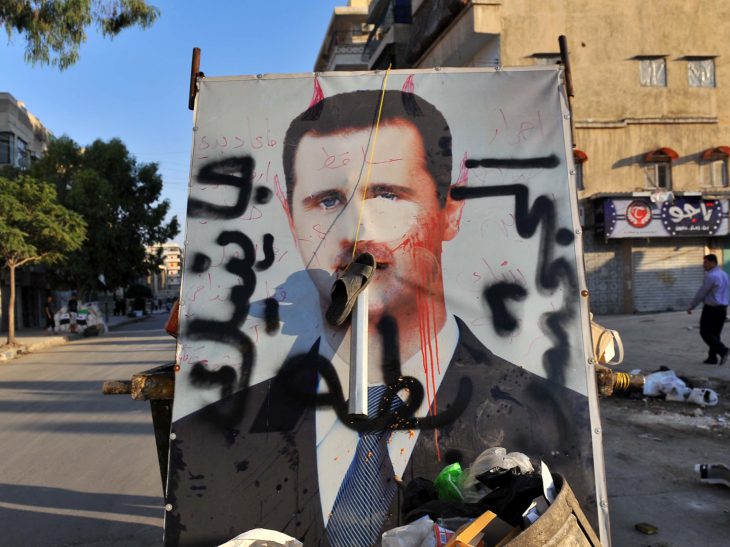

At the end of last month, on June 28, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan once again showed his willingness to meet Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Referring to the period before the deterioration of relations, he expressed his desire to bring relations with Syria to the same point. Days after Erdoğan's statement, CHP spokesperson Deniz Yücel announced that CHP Chairman Özgür Özel will meet with Bashar al-Assad in July.

According to media reports, the refugee issue is expected to be the first item on Özel's agenda, but Turkey's military presence in Syria and its relations with armed organizations are also expected to be the Syrian side's priority issues. Likewise, in July last year, Erdoğan's statements that he was open to talks with Assad were met with Assad's precondition of Turkey's withdrawal from Syria. In response, Erdogan's attempts to open up Syria continue. So, how should one explain this apparent shift in Erdoğan's attitude towards Syria? In this article, I will briefly try to answer this question.

Since this answer cannot be given only as a foreign policy debate, I will try to explain these changes of direction, which are sometimes described as u-turns, inconsistencies and failures in the Erdoğan administration's politics, within the framework of the Erdoğan administration's unique logic of reproducing its power.

Throughout the article, I will try to offer this explanation within the framework of the claim that the test with the Kurdish issue lies at the center of the Erdoğan administration's domestic and foreign policies and even the way it relates to global capitalism. In order to draw such a comprehensive picture, it is actually necessary to go back a long way and trace the conditions and policies that brought the Erdoğan administration to the present day. But since the scope of this article does not allow for this, I will take the story of Erdoğan's rule from the early 2010s to show how the Kurdish issue has become the main determinant of Erdoğan's and his AKP's strategy to reproduce its power in the post-2015 period.

2011-2013 PERIOD AND THE DEVELOPMENTS THAT FOLLOWED THEM

Although Erdoğan and his AKP reached the peak of their power in the 2011-2013 period, this period also marks the beginning of a period of drift determined by a series of developments and their responses to these developments. From 2011 onwards, Erdoğan's coalition with Fetullah Gülen showed signs of fracturing, leading to the December 17-25 corruption operations at the end of 2013 and the coup attempt in July 2016. The Gezi Park protests in 2013 severely shook Erdoğan's leadership and, together with the coup in Egypt, significantly shaped the perception of risk. In May 2013, as the Federal Reserve began to tighten monetary policy, the flow of cheap and abundant financial resources, one of the main pillars of Erdoğan's rule, was diminishing. At a time when the Obama administration in the United States was relatively reluctant to embark on new military adventures in the Middle East, the Erdogan administration tried to determine the direction of the social movements commonly referred to as the Arab Spring, especially in Egypt and Syria, and gradually became increasingly isolated in its Middle East policy. In Syria, Erdoğan adopted a policy of regime change and tried to unite armed opposition organizations under one roof with Turkey's support. By June 2015, Erdoğan and his AKP failed to win a parliamentary majority for the first time. At the same time, the "solution process" that had been underway for some time was beginning to collapse. With the HDP's refusal to support Erdogan's presidency and the PYD's refusal to join the armed Islamist organizations in Syria that Turkey was supporting, the "resolution process" was completely shelved and the Kurdish issue once again became the main determinant of Turkey's domestic and foreign policy.MILITARY OPERATIONS IN SYRIA HAVE AFFECTED RELATIONS WITH THE US

Seeing no other possibility to reproduce his power within Turkey, Erdoğan became the face of an ultra-nationalist coalition, whose main motivation and goal, both in domestic and foreign policy, was to prevent the Kurds from gaining any status. While the Kurds' right to political representation was effectively eliminated on local and national scales by means of trustees, trials, arrests and other means at home, it has tried to prevent the control of the Autonomous Administration of Northern and Eastern Syria through a series of operations in Syria since 2016. The Erdogan administration, which linked the US with the coup attempt and the PYD's gains in northern Syria, expanded its control over Syrian territory along the border, first west of the Euphrates and then east of the Euphrates, after failing to find the support it wanted from the Trump administration on Syria after the Obama administration. Of course, in doing so, it has been careful not to completely cut ties with the US while maintaining a relative rapprochement with Russia and Iran. The US reluctance to play a more active role in the Middle East and Russia's desire to take advantage of Turkey's deteriorating relations with the US have given the Erdoğan administration more room to maneuver. On the other hand, neither the US nor Russia gave the green light to the expansion of Turkey's operations to fully control a 30 km deep swath of Syrian territory along the border line.ECONOMIC POLITICS AND THE NATIONALIST COALITION

In sum, the Kurdish issue has played a decisive role in the Erdogan administration, not only in its Middle East policy, but also in the general direction of its foreign policy, domestic politics and economic policy. The loss of the parliamentary majority in 2015, coupled with the failure of the resolution process, has since led to a constant risk assessment of the loss of voter support. Together with the loss of the support of Gulenists in the state cadres, this made an alliance with nationalists inevitable in the eyes of the Erdoğan administration. The operational logic of this alliance has made preventing the Kurds from gaining a political status either inside or outside the country the main objective. Considering the function of access to cheap credit in securing the electoral support of Erdoğan and his AKP for many years, its drying up since 2013, with some exceptional periods, led to the filling of that function with nationalist rhetoric and practice. It was this independenceist, nationalist rhetoric and practice that legitimized the Erdogan administration's turning its back on the US and the West to a certain extent, weakening its ties with Western finance and implementing policies that supported its own capital base and impoverished large parts of society. In the same period, with the relative withdrawal of the US, the Erdoğan administration found more room to act more freely. While Turkey is unlikely to conduct "comprehensive operations" in Syria as long as the US partnership with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continues, the Erdogan administration may seek to create favorable opportunities, especially in a potential Trump administration.IRAQ POLICY AND CONFLICT WITH PKK

The situation is different in Iraqi Kurdistan. Turkey has been systematically increasing its military presence there for a long time and seems to have the support, or at least the passive support, of the Kurdistan government. Moreover, unlike the SDF, the organization targeted in Iraqi Kurdistan is the PKK, which is designated as a terrorist organization by the US and other Western countries. In this way, the two situations differ in certain respects in terms of international legitimacy. Therefore, it is impossible to understand Turkey's economic, political and international policy independently of the Erdoğan administration's stance on the Kurdish issue. The turn in Syria policy should not be seen as a reversal of a mistake, as the mainstream opposition sometimes does, but as a manifestation of the decisive role that maintaining the position on the Kurdish issue plays in all other policy-making. Erdoğan's willingness to meet with Assad is not about solving the refugee issue, as the opposition assumes, but about preventing the Kurds from gaining political status. In this sense, the CHP's and the AKP's motivations for meeting with Assad diverge. In any case, Erdogan's regime change plan seems to have disappeared. In Iraq, as long as the Kurdistan Regional Government remains within the borders drawn by Erdoğan, Turkey's relations with Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan are unlikely to change much. In conclusion, we can assume for the near future that as long as the Erdoğan administration needs the support of the nationalist front that it clings to in order to reproduce its power, the stance on the Kurdish issue will continue to play a decisive role in domestic and foreign politics.*Can Cemgil: He is a faculty member at Istanbul Bilgi University, Department of International Relations. Cemgil received his PhD from the University of Sussex in the UK and his research interests include International Relations Theory, Social Theory, International Political Economy, Turkey's Foreign Policy, World Politics and Geopolitics of the Middle East. His most recent works include Capitalism and Democracy: Anatomy of an Opposition.