Asli Aydintasbas: Topple, tame, trade: How Turkey is rewriting Syria’s future

asli aydintasbas

asli aydintasbas

Turkey didn’t orchestrate Assad’s fall, but it’s certainly cashing in on the aftermath. Now, it wants to mould Syria in its own image—if it can keep the Kurds from spoiling the party..

The lightning offensive that led to the downfall of the regime was not organised by Turkey, but it also couldn’t have happened without Ankara’s approval and tacit support. This gives Turkish leaders a say in Syria’s future direction. Their intentions in Syria will also serve European interests—provided the parties arrive at a peaceful formula to find a place for the Kurds in the country.

Turkey’s sway

HTS is not one of Turkey’s direct proxies inside the rebel camp. But the group had long cultivated a close working relationship with Ankara because the rebels controlled Idlib, a province on the Turkish border in northern Syria. The three million Syrians living in Idlib have depended on Turkey for international aid and security.

In time, Turkish officials developed a relationship with the enigmatic leader of HTS and now Syria’s transitional president, Ahmed al-Sharaa. This gives Ankara substantial leverage over the group.

Turkey’s leaders now seek to shape Syria’s future governance, not just in terms of stability but also in moulding a system that reflects its own political ethos. Turkish conservative elites would be comfortable with Syria emerging as an image of Turkey itself: conservative, competitive and centralised—even if it means a conservative Sunni majority dominates the political landscape.

Still, Turkish politicians have been urging Syria’s new leaders to establish an “inclusive” transitional government that can stabilise relations with the country’s disparate communities, ranging from Kurds to the Druze, and meet international demands for representation and moderation.

Islamist radicalism

The question of moderation and tolerance in Syria is tied to whether the country’s new rulers are still jihadists at heart. Sharaa has both the Islamic State group (ISIS) and al-Qaeda on his resume, even though HTS ended up fighting both of them. According to Turkish officials I interviewed, Turkey’s sway in northern Syria helped moderate HTS in its governance of Idlib.

Turkey’s leaders seem to believe Shaara is pragmatic enough to heed the demands of Damascene elites and Syrian minority communities, as well as regional powers, and not push ahead with a purist Salafist agenda. “He understands Idlib is Idlib and Damascus is Damascus,” a leading Syrian opposition figure with close ties to Ankara told me. Shaara’s ambition, he argued, is to effectively govern Syria and be elected as the president, not play a destabilising role or export Islamism. Ultimately, Turkish leaders want the new Syrian government to have international legitimacy and its leader to demonstrate credibility; they do not want a pariah state on their border.

Economic influence

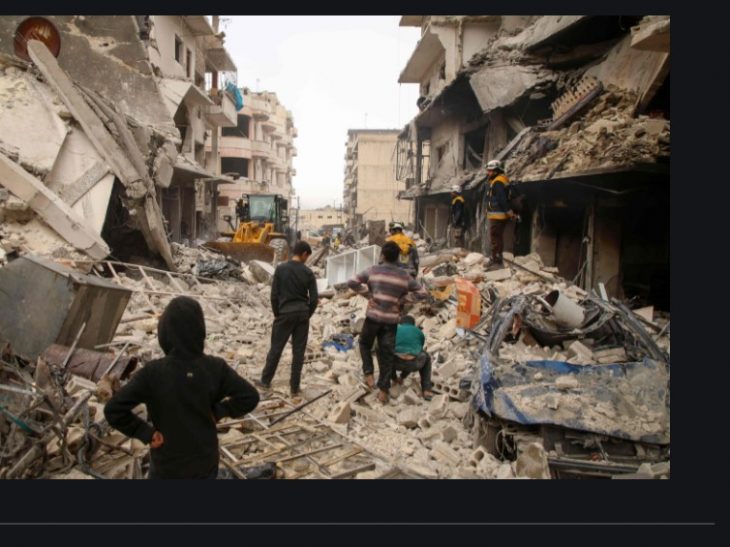

Beyond ideology and governance, Turkey’s stake in Syria is deeply economic. The fall of Assad’s regime has opened up lucrative opportunities. Although Turkey lacks the money to rebuild the war-torn country, it has a large construction industry, consumer goods and already is the dominant economic actor in northern Syria. Stock prices for Turkey’s construction companies soared with the news of Assad’s downfall as they will benefit enormously from Syrian reconstruction.

Erdogan instructed his ministers of energy and transport to help with the early recovery efforts in Syria’s decrepit energy and infrastructure system. Turkish leaders seem eager to lay the groundwork for a success story out of the ashes of the collapsed Baathist regime. Success would expand Turkey’s zone of influence and provide Syria with international legitimacy.

The Kurds

However, stability in Syria is not just about reconstruction. It also hinges on resolving the Kurdish question. Here, Turkish priorities diverge sharply from those of the Syrian Kurds and their Western backers.

One of Turkey’s top concerns in Syria is how much autonomy the Kurds will get, given that the question is now intertwined with the Kurdish issue in Turkey.

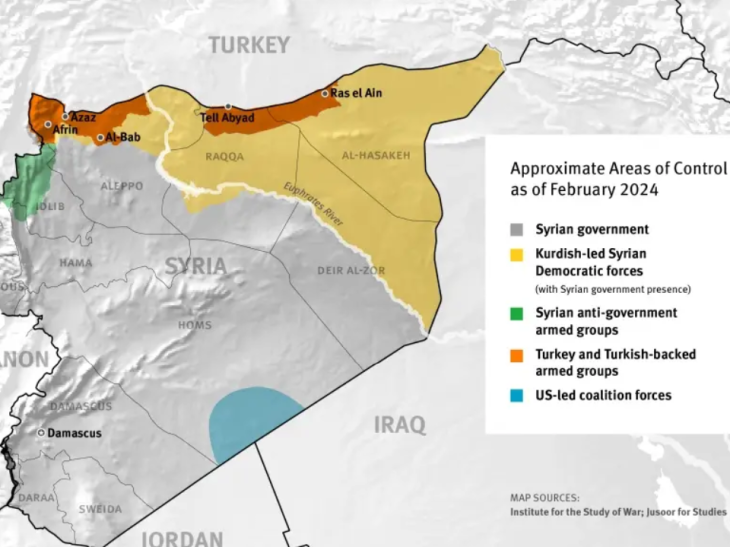

The Turkish government considers the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a militant group that both America and Turkey designate as a terrorist organisation. The SDF has a military force of roughly 100,000 men and women, and its self-declared autonomous administration covers a third of Syria’s territory and 70% of oil and gas resources. Ankara sees Kurdish self-rule as a threat to its unitary structure.

The USA is the fly in the ointment

But Turkey has a problem. America has 2,000 troops embedded with the SDF. Despite numerous military operations in Syria and diplomatic feuds with the US, Turkey has been unable to sever Washington’s relationship with the group. The rapid downfall of the Syrian regime and the arrival of Donald Trump, however, may give Ankara a chance to limit the Kurds’ autonomy. If Trump keeps the US troops in Syria, Turkey will not be able to impose full military pressure on the SDF. The Kurds will undoubtedly have a stronger negotiating position and be less willing to compromise. If the US pulls out, or even announces a withdrawal timeline, the SDF will be under greater pressure to compromise on its political demands or risk future Turkish incursions from the north.

Turkey opposes an Iraqi-style loose federalism in Syria, despite its close alliance with Iraqi Kurdistan. Instead, it demands that the SDF be integrated into the Syrian military under a centralised command and the PKK-linked senior cadres inside the group be expelled from Syria.

On this issue, Turkey and the new leaders of Syria seem to be on the same page. There is also a broad consensus between Ankara and Damascus that the Kurds should not maintain their extensive geographic control, which now includes Arab-majority towns like Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor.

Having enjoyed self-rule for nearly a decade, the Kurds seem determined to push for a more decentralised governance model than either Turkey or Damascus would like—one where a Kurdish region can have, not just cultural but also administrative and military control. Kurdish sources claim that the SDF is open to swapping Arab majority territory and energy resources for a more decentralised rule.

The European interest

Migration, ISIS remnants, and regional stability make Syria a concern for the EU, but the bloc lacks the military and political leverage to shape the country’s future directly. Turkey, by contrast, is positioned to do so—and will. Working with Turkey as the main conduit to Syria’s economic and political development is the best option.

Yet Brussels and Ankara may differ on the Kurdish question. Europeans and other regional players like Israel would prefer a strong Kurdish entity in the heart of the Levant due to Kurdish society’s secular nature, the Kurdish-US extensive partnership against ISIS, the shared apprehension of a radical Damascus, and European dedication to minority rights and self-determination.

But managing the Turkish-Kurdish dynamic towards a peaceful settlement inside Syria may simply be outside of Europe’s reach. One option is to offer Turkey and Syria economic incentives and diplomatic backing in exchange for moderation in governance and minority rights.

This is an excerpt from the same-titled essay by Asli Aydintasbas. The source, European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.

IMPORTANT DİSCLOSURE: PA Turkey intends to inform Turkey watchers with diverse views and opinions. Articles in our website may not necessarily represent the view of our editorial board or count as endorsement.

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/