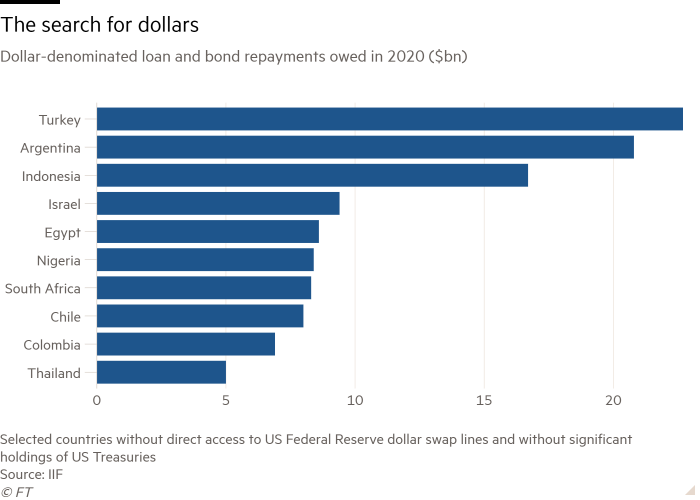

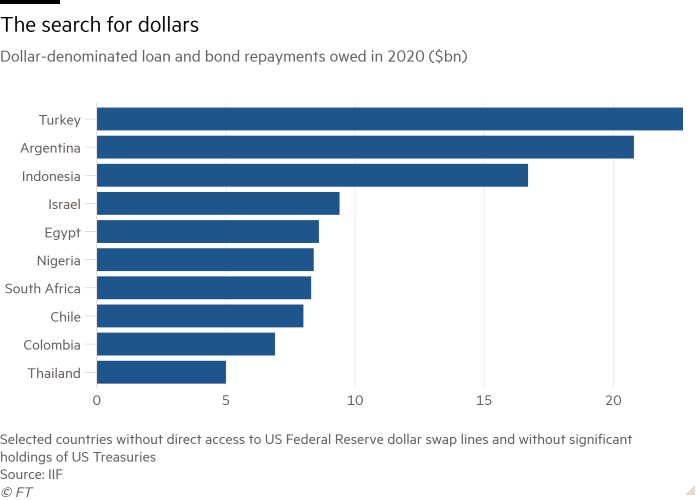

The broadest-ever effort to pump dollars into the global economy has bypassed some major emerging markets, leaving them struggling to get their hands on the liquidity they need, according to analysts. As the Financial Times outlines, Turkey stands at the top of the list.

The US Federal Reserve and the IMF have both launched schemes to lend dollars to countries in need as part of their efforts to help combat the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic. For example, the Fed’s temporary dollar swap lines cover 14 central banks, including those of Brazil, Mexico, South Korea and Singapore.

But nations including Turkey, South Africa, Nigeria and Indonesia are all shut out of the system, despite having heavy dollar-based financing needs.

Countries need dollars to cover current account deficits, repay external borrowing and to provide liquidity to their banking systems.

Many states are struggling with a toxic brew of portfolio outflows, falling hard-currency export revenues and collapsing tourism industries.

Brad Setser, senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations, said the Fed’s schemes were of little help to countries such as Turkey, South Africa, Lebanon or Indonesia, while the IMF’s response “still strikes me as inadequate”, leaving some countries to “look around for options that they don’t have”.

Distributing the dollar

The US Federal Reserve and the IMF have several options for countries seeking access to dollars.

The Fed’s dollar swap lines — launched in March — are an expanded version of its effort during the financial crisis to pump dollars into the global economy. The Fed has also created a repurchase facility that lets foreign central banks trade their US Treasury holdings for dollars.

Last month the IMF unveiled a short-term liquidity line facility, the first addition to its financing toolkit for almost a decade, to help emerging countries faced with a sudden stop in funding. The fund already offers a longer-term flexible credit line.

The Fed has traditionally offered dollar swap lines to central banks from countries with strong economic fundamentals and independent central banks, criteria that limit the pool of beneficiaries.

“In general [these facilities] help the countries that don’t really need help,” said Tim Ash, a strategist at BlueBay Asset Management. “The Fed gives it to countries with good policies, and the countries with good policies the markets like anyway.”

Among those countries that may struggle to access dollars, Turkey faces one of the toughest repayment schedules, with $22.7bn of dollar-denominated sovereign and corporate bonds and loans repayable this year, according to data from the Institute of International Finance. Argentina has $20.8bn of dollar debt due over the same period, with Indonesia due to repay $16.7bn, Nigeria $8.4bn, South Africa $8.3bn and Colombia $6.9bn, IIF data show.

Charles Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, an emerging markets-focused investment bank, said he feared for countries such as Mozambique and Zambia, where “I was hearing . . . there are problems getting [dollars] anywhere in these countries”, and Iran, Venezuela and Nigeria.

Other countries that may struggle to access either scheme include Colombia, Indonesia and South Africa, according to Mr Ash.

Paul Greer, portfolio manager at Fidelity International, flagged the plight of some EM economies that use the US dollar as domestic currency, such as Ecuador, which face competitiveness issues as the currencies of their trading partners depreciate.

While the Fed’s swap lines are only available to a small number of emerging countries, its repo lines are in theory available to all. But in practice they are only of much use to countries with a large stockpile of foreign reserves that has been invested in US Treasuries.

China, in little need of enhanced liquidity, had at least $1.1tn of Treasuries under custody at the Federal Reserve as of February, according to US Treasury data. Similarly Brazil, beneficiary of a Fed swap line, had $286bn. Hong Kong, which has been buying additional dollars to stop its currency strengthening above its peg, had $250bn, Taiwan $202bn, Saudi Arabia $184bn, India $178bn and Singapore $165bn.

Yet, among countries without access to swap lines, Turkey had just $2.3bn of Treasuries according to the US Treasury data, South Africa $14.2bn, Indonesia $28bn, Oman $7.4bn, financially troubled Argentina $6.5bn and Venezuela just $294m.

“So far there hasn’t been heavy use of this [repo] line,” said Mr Setser. “It’s priced pretty steeply. It’s more of a backstop at the moment. It doesn’t solve the problem of [countries having] too few reserves.”

Emerging economies hold back on asking creditors for debt relief

Hung Tran, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance, feared that many emerging markets would not qualify for the IMF credit lines because they lacked a “strong macro policy track record”, while some countries that do have access may shy away from these programmes because they “suffer from a perceived stigma effect”.

Mr Ash said: “You can question whether South Africa qualifies. Very strong policy and fundamentals? I don’t think so.”

Similarly, Turkey would appear to fall foul of the Fed’s sound monetary policy rule, given president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s interference in the running of the central bank. The bank’s governor, Murat Uysal, said last month that Turkey was holding talks with other G20 nations about swap lines but so far no announcements have been forthcoming.

Some economists believe Turkey will ultimately have little choice but to ask the IMF to provide a full standby agreement — even though senior officials have repeatedly ruled it out.

Selva Demiralp, a professor of economics at Istanbul’s Koç University, said that the pressure on the Turkish lira — which recently hit an all-time low — was creating an increasingly urgent need for policymakers to secure some kind of outside help.

“I really don’t think they can wait very long,” she said. “I would think that a deal, in whatever form, should be coming very soon.”

FT