This article penned by MITALI DAS, ŞEBNEM KALEMLI-ÖZCAN, DAMIEN PUY and LILIANA VARELA and published in Project Syndicate was also translated in Turkey’s dissident news portals as a warning for Turkey, which the authors rated among the worst three in terms of debt sustainability. With corporate and consumer debt growing at an annualized rate 103% and 43% respectively, while Central Bank’s Monthly Expectations Survey predicts 1.2% recession for 2020, the article needs to be read carefully. Compounding Turkey’s difficulties is the continuous decline in CBT’s FX reserves which declined to $81 bn in last data week, or less than half of Turkey’s foreign debt maturing in the next 12 months (ca $170 bn). Yet, Turkey’s greatest problem is not its balance sheet, but an administration which denies that there is a problem, clinging to wild goose chases for swap lines, import taxes and soft capital controls to kick the can down the street, rather than initiating reform to resolve the dual threats of debt and currency crisis.

Currency slump in EMs

When an EM currency depreciates, that country’s foreign-currency-denominated debt burden – both its absolute value and debt-service costs – can escalate rapidly. Such balance-sheet effects often presage corporate defaults, financial instability, and output declines, as we saw during previous EM crises.

In devising an appropriate economic policy response to COVID-19, therefore, EM policymakers must answer a key question: how much financial trouble linked to balance-sheet effects is this wave of currency depreciations likely to cause? Estimating the potential damage is complicated by the fact that the magnitude of unhedged FX debt in EMs is hard to pin down.

Over the last 40 years, the debt landscape in EMs has changed dramatically. On one hand, EM governments have significantly reduced the extent of their “original sin” of relying on FX borrowing, owing to improved macroeconomic fundamentals and better fiscal and monetary discipline.

The corporate borrowing binge

In the meantime, however, EM companies have gone in the opposite direction: as it became cheaper for these firms to borrow in global currencies, their FX borrowing grew. And recent research shows that when the cost of borrowing in foreign currency drops, more firms issue FX debt.

This migration of FX exposure from EM sovereigns to corporate borrowers has brought new challenges. In particular, private firms’ finances are less regulated than those of governments and banks, so we know much less about their balance sheets.

Who are the doomed sinners?

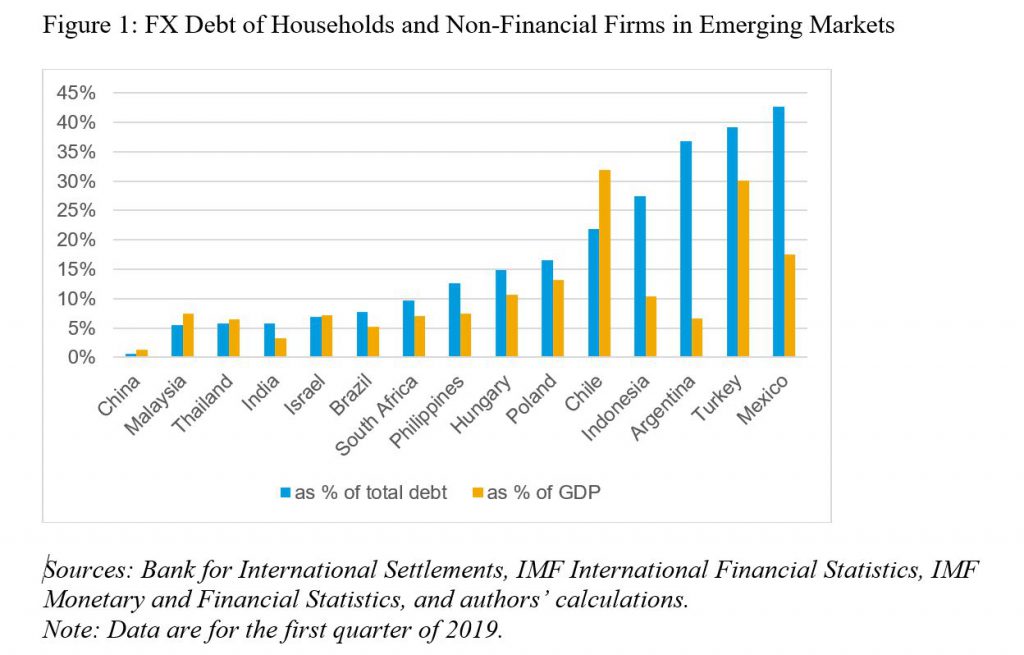

Nonetheless, our research – using a variety of private and public sources – gives a sense of the magnitudes involved. Figure 1 shows the FX debt of households and non-financial firms in major EMs, both as a share of their total debt and as a share of GDP.

Encouragingly, Figure 1 suggests that private-sector FX borrowing in many EMs might be relatively limited. With a few exceptions (notably Turkey, Mexico, and Argentina), most countries have manageable levels of private-sector FX exposure relative to total debt. More important, this “raw” measure should be viewed as an upper bound of the FX debt problem in EMs.

Because many EMs with high FX exposure are large commodity exporters (such as Mexico and Chile), the numbers in Figure 1 might overstate the actual size of the problem.

The bad news is not only that this type of natural hedging may provide no buffer in the current environment of low commodity prices, but also that EM firms in non-tradable sectors could have substantial unhedged FX borrowing on their balance sheets. Although there is no systematic data regarding these companies’ use of FX derivatives to hedge foreign-currency debt, evidence from Hungary (albeit based on data from before 2010), Chile, and Turkey indicates that non-financial firms borrowing in foreign currency use such instruments infrequently.

The real problem: Loans in non-tradable sectors

And, the share of foreign-currency loans in non-tradable sectors has risen to about 40% in Hungary and Peru (for construction), and around 50% in Turkey and Mexico (for services).

The high levels of unhedged FX debt among private-sector EM firms are particularly worrisome in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. With significantly reduced income and sales, such firms will struggle to repay debt, and some might default. That would jeopardize financial stability, because most FX borrowing is intermediated through domestic financial systems.

We know surprisingly little about the extent of this problem in EMs. A common practice is to take central-bank FX reserves as a measure of a country’s preparedness to fight a capital-flow reversal. But such an approach may offer false comfort, because it is impossible to know whether reserves adequately cover unhedged FX debt in the private sector.

Excerpt only, read the full article here

You can follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/