A more positive relationship between the European Union and Turkey is a decade-long project of advocates from all over Europe and across the Atlantic. Drawing on history, witnesses see how this relationship can be an excellent win-win algorithm, as much as it can rapidly turn out to be a lose-lose situation or even a triple win-or-lose equation—with political, economic, and social resonance reaching far beyond the Continent.

The challenge is to upload this historically well-tested algorithm into the twenty-first century: rebooting a version 5.0 of Turkey’s European integration with updates on democratic conditionality, foreign policy cooperation, and an economic framework, as well as on the digital, green, and social dimensions.

The Turkey debate’s focal point is “Europe’s geostrategic sovereignty.” Turkey should evolve to be a net contributor to Europe’s security and global competitiveness. No matter how significant today’s drawbacks, such as freedom of expression and tensions like the life-consuming Cyprus imbroglio, the guiding question for the EU ought to be: “how can Turkey, in the near future, become a country that is progressively in convergence with the values and interests of European citizens?” This includes citizens of the Turkey as well.

Problems? Tensions?

Political tensions between Turkey and the EU are real, challenging, and harmful. However, nonconstructive policies of engagement also are part of the problem. They have been stimulated by years of ever weaker partnership, deadlocks, prejudices, and policy errors from both sides. Thus, we cannot find in more negative policies—blocking, suspending, or sanctioning different aspects of the EU-Turkey relationship— a relevant solution to contemporary problems. As Albert Einstein would have said: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Excluding Turkey from Europe has been very costly for citizens of both the EU and Turkey. If Turkey had been deeply, skillfully engaged—on issues such as foreign policy, rule of law, refugees, economic growth and energy policy—when the open-ended accession negotiations began in 2005, the sequel today would be much different. Including Turkey would have strengthened the EU as a global power and would have contributed to the development of Turkey as a European democracy in convergence with European values and interests.

WATCH: Real Turkey feat Bahadir Kaleagasi: Turkey and Russia in Biden Era

It’s Democracy . . .

Globalization prompts increased mobility and prosperity to human civilization, but also stimulates us to be more innovative to deal with global viruses of all kinds: biological, digital, and financial; the disinformation virus contaminating our democracies; and also the viruses of terrorism, organized crime, corruption, and unemployment. Most importantly, the CO2 virus endangers the human civilization.

In this context, Europe’s future is marked by existential questions. Shall European states ultimately commit to a prerequisite level of coherence and solidarity to craft the EU’s new global role? Will there be agreement to transfer more effective economic policy competences from member states to the EU’s supranational level? How can Europe continue to generate soft power for a more democratic, greener, human- centric, and safer world?

Turkey can be a part of the answer for these questions. The only realistic strategy for Turkey’s global competitiveness is to reposition itself as the West’s Eurasian gateway of democracy, economic dynamism, and social progress.

EU capitals, including Athens and Nicosia, can either be idealistic or realistic. However, both ways of thinking point toward more benefits from reengaging Turkey in the integration process, including conditionalities on concluding, not initiating, different phases such as a modernized customs union. Maybe there also is a third way: short-sighted populism. There is enough historical evidence to argue that the more Turkey is excluded from the EU’s sphere of influence, the more it becomes part of the problems which in turn nourish populistic demagogy and threats to Western democracy. In the end, the main purpose of all these recommendations is the search for a better twenty-first century democracy.

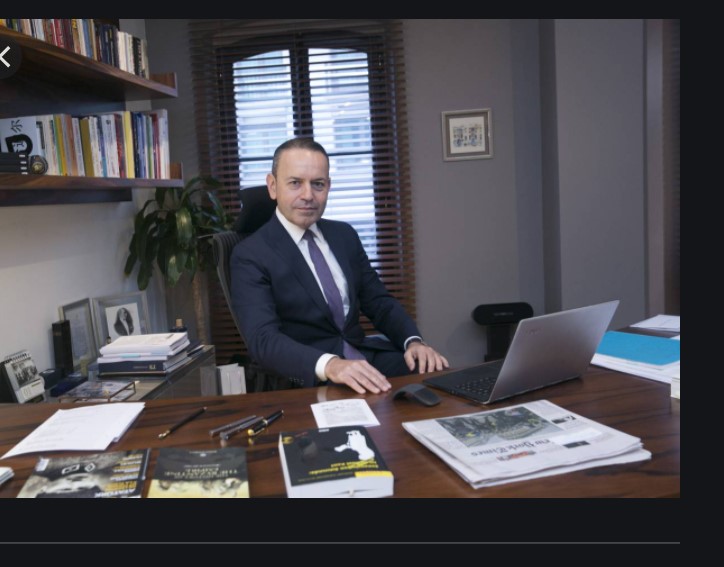

Dr. Bahadir Kaleagasi is president of the Paris Bosphorus Institute, lecturer at the Galatasaray University in Istanbul, Brussels Energy Club’s honorary chairperson, and board member of or adviser to several companies, think tanks, and nongovernmental organizations. He was formerly an academic at Université Libre de Bruxelles, researcher for the European Commission’s Forward Studies Unit, successively EU representative, international coordinator, and CEO of Turkey’s main business association, TUSIAD, and executive board member of BusinessEurope (The Confederation of European Business). He is author of several books on international affairs, sustainable development, and Turkey.

This is an excerpt from the similarly titled article, the link to full document is here