In the summer of 2013, groups of Turkish citizens gathered in Istanbul’s Gezi Park to protest the government’s development plan for the park which included a new mall and luxury apartments.

The plan came at a time when Turkey’s economy was struggling, unemployment was high, the war across the border in Syria was raging, and Turkey’s longtime ruling party, the AKP, was governing with an increasingly heavier hand.

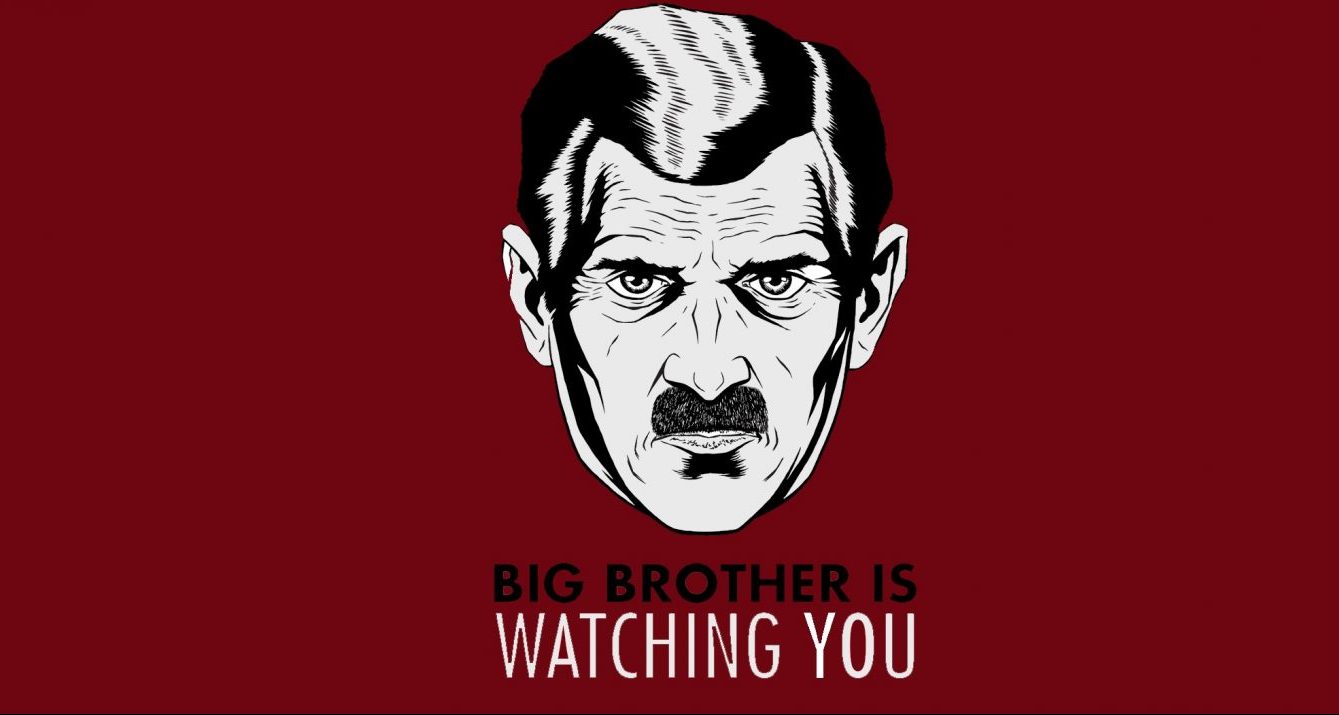

Turkish citizens were seeing a growing authoritarianism in their country: greater restrictions on public behaviour, a clamping down on free expression especially anti-state or anti-religious views, and a growing sense that only a supporter of the ruling party was a good citizen.

It seemed like the kind of restrictions and surveillance historically felt by Turkey’s minorities — especially Kurds — was now pervasive and normalized.

Those protests grew to an estimated 3.5 million people across the country. The state’s response to the Gezi Park protests was swift and brutal. Turkish citizens say Gezi Park felt like a moment of shift.

Turkey is hardly the only country facing what experts call “democratic backsliding.”

Looking at a map of the world, it’s clear in the last 30 years the presence, demise, and return of authoritarian governments has contracted and expanded like an accordion.

Despite this decades-long turn, the rise of Donald Trump in the United States came as a shock and signalled that even the longest-standing democracy of modern times was not safe.

The strongman, long associated with the dictators and tyrants of the postcolonial world, had now found his way to the rich west.

cbc.ca