Syria has recently become quiet, as Assad’s government ran out of financial resources, while Covid-19 hit the country hard. However, the conflict is very likely to be rejoined soon, as the question of the Idlib province remains unresolved. Turkey can’t abandon Syria to Assad, which will be very destabilizing to her border region. Turkey has also an almost paranoid fear of Kurds in Northeastern Syria, who are denied trade opportunities, as daily skirmishes continue to take lives. Where is the conflict heading and what can US and EU do to facilitate peace?

Max Hoffman and Alan Makovsky of CfAP address these issues in a lengthy analysis.

“This decadelong conflict has shredded the already threadbare idea that the international community can come together—even at the level of the lowest common denominator—to manage cataclysms of this sort. It has precipitated Russia’s violent return to the region, as part of a wider internationalization of the conflict that has sharpened sectarian divides. This, in turn, has made U.N. activities—and the wider provision of humanitarian assistance—into yet another front in the core struggle between the illegitimacy and durability of the Bashar Assad regime. The international community has a political and moral imperative to address this crisis” comment the authors.

PA Turkey presents critical paragraphs from the report

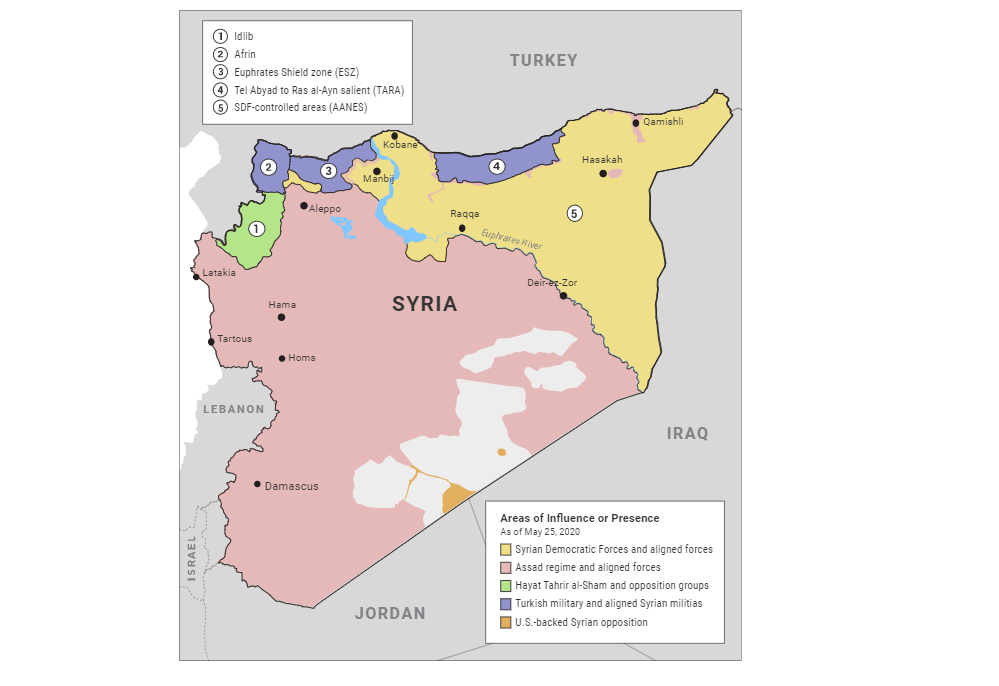

What started in 2011 as peaceful protests of the Assad regime’s authoritarianism and corruption morphed into civil conflict in the face of the regime’s brutal repression. By 2012, Syria was gripped by full-scale civil war. The internationalization of the conflict proceeded apace from 2013 to 2015, with regional actors such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar pouring in money and war materiel to support the rebels; Russia and Iran escalating direct military support for Assad; and the United States and its key European allies cautiously vetting and arming small opposition groups. The rise of the Islamic State group (IS) prompted a more forceful U.S. and European response from the end of 2014, sparking an aerial campaign in support of mainly Kurdish partner forces fighting IS on the ground in a largely separate campaign in northern and eastern Syria. The ascendance of these Kurdish forces in 2015 and 2016—along with the arrival of millions of Syrian refugees into Turkey—in turn prompted a more forceful Turkish line from late 2016, with a series of direct military interventions carving out Turkish-controlled areas in northern Syria. The war has now settled into an uneasy stasis, with Syria divided broadly into three spheres of influence: regime-controlled, Turkish-controlled, and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)-controlled. The complexities of these zones are considered in detail in subsequent sections.

Defined narrowly, the United States has limited interests in Syria, which for some extend only to preventing the country from being a base for international terrorist activity. But as U.S. military, diplomatic, and intelligence officials—not to mention people from the region—consistently underline, even this basic interest is not secured without some broader stability. A more expansive view, incorporating a more values-driven approach, would therefore extend to alleviating human suffering where possible and de-escalating the conflict to allow for basic stabilization. For some, this values-driven approach further demands continued solidarity with the local partners who fought and died to destroy IS. Equally, European states can choose to define their interests narrowly—to focus exclusively on counterterrorism and preventing out-migration from Syria. But this desire to limit European involvement and exposure will run into the same reality: These limited goals are not likely to be realized without broader de-escalation and stabilization.

RELATED

The First 100 Days: Toward a More Sustainable and Values-Based National Security Approach

Interactive: The First 100 Days

The Biden administration, in concert with European allies, should seek to address this crisis as part of a broader effort to de-escalate regional conflicts and reconstitute some semblance of international cooperation. This interest should go beyond the laser-like focus on counterterrorism that dominated the Obama administration’s approach. Still less should the new team embrace the confused realpolitik—punctuated by chaotic presidential actions—and disinvestment that characterized the Trump administration. Nor should American interests be framed solely by a hackneyed conception of great power competition wherein rivals’ every commitment must be matched by counter-commitments. U.S. involvement in Syria is important not only because Russia is there, nor simply as a way to check Iran’s malign influence in the region; it is primarily important because the conflict is causing massive humanitarian suffering, crippling U.S. allies and partners, and eroding the international system. The United States can, working with partners on the ground and mobilizing international support, make a meaningful difference in the conflict at minimal cost—it is both the right and the strategic thing to do.

In northeast Syria, where American partners hold sway, the situation on the ground is hugely complicated, but the assessment of U.S. interests is simpler: If narrowly defined, the United States could potentially pull out and rely on airstrikes on terrorist targets, leaving Syria to fester as a source of continued suffering and instability. Defined more broadly, the United States should stay. Counterterrorism, humanitarian conditions, stabilization, solidarity with partners, and the prospects for reconciliation are all best advanced by a continued American presence, one that can be sustained with manageable risks and limited costs. Besides Turkey, the United States is the only Western power playing a meaningful role shaping security dynamics in Syria. Despite the leverage squandered by President Donald Trump’s partial withdrawal, the United States remains indispensable for the influence it wields over Kurdish forces; the intelligence and surveillance assets it brings to bear; and the deterrent effect it can have on the Assad regime, Russia, and Iran. Indeed, the United States is perhaps the only Western power capable of stopping a new phase of fighting in Syria and precluding a resurgent IS insurgency. For Europe, the smart policy would be to support expanded stabilization under the security umbrella provided primarily by the United States, with France and the United Kingdom’s assistance.

In the Turkish-controlled zones, the form of U.S. and European engagement is different, bringing important values and principles into conflict. As this report details, Turkey has asserted de facto sovereignty over its zones of control to undermine Syrian Kurdish autonomy, prevent further refugee outflows, and allow for the resettlement of refugees from Turkey itself. Turkey is not likely to leave in the foreseeable future, and its actions effectively end prospects that Syria will reemerge as a unitary state in the near term. Of course, Syria was already effectively divided, and sovereignty is not absolute; Assad sacrificed any legitimacy when he barrel-bombed, tortured, and gassed his own people. Nonetheless, the United States and Europe must weigh whether to effectively endorse the potentially permanent occupation of between 2,800 and 4,000 square miles, if Idlib is included, of Syrian territory by Turkey. Internationalizing the management of this area might offer a promising path if it were possible, but it is a distant prospect; Russia has paralyzed the U.N. system on Syria, and Turkey wants to maintain its control.

The long-term risks inherent in Turkey’s efforts to create refugee resettlement zones by force—massive demographic change, radicalization, and long-term instability—are of profound interest to both Turkey and Europe and of serious interest to the United States. Yet Europe is largely absent on this front. Given the scale of the challenge in providing basic services and humanitarian assistance to displaced Syrians—both within Syria and beyond, including in Turkey—let alone the problem of reconstruction, Turkey will need the support of both the United States and the European Union. Turkey is a front-line state dealing with the spillover from the conflict and has deemed EU and U.S. support insufficient. Despite years of sharp disagreement on the right response in Syria, without question, Turkey, the European Union, and the United States would benefit from each other’s support.

WATCH: Turkey’s Convoluted Foreign Relations | Real Turkey

For Europe, the interests are not just humanitarian, nor just the sometimes-cynical approach to migration and associated political fear of right-wing populism at home. Europe’s interest is in a stable, democratic Turkey with which it can trade and manage shared challenges. Turkey has decided—to the chagrin of some in the West—that it cannot insulate itself against the spillover from the Syrian war, nor manage its domestic Kurdish problem, without becoming an active combatant. Given this reality, to be a meaningful player in this space, the European Union needs a credible, well-financed, and politically realistic approach that goes beyond its current assistance in and to Turkey. The European Union and Turkey share vital moral, political, and strategic interests in ensuring that Turkey manages this challenge effectively and humanely. Like Europe, the United States has an interest in a stable, democratic Turkey with which it can manage shared security challenges. However distant that goal is today, Turkey’s long-term stability—likely beyond President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rule—will be severely undermined if it cannot manage its integration challenge at home or if the refugee zones it has created along its border remain volatile exporters of insecurity and entrenched sources of human misery.

Yet Turkey’s unilateral military actions have not been purely humanitarian. Ankara has sought to weaken Syrian Kurdish actors and change the demographic balance of northern Syria, and Turkish interventions have caused additional suffering and displacement in some places, though the Assad regime’s eventual return would have done likewise. Ankara’s Syrian rebel proxies in these actions include ill-disciplined radical groups credibly accused of human rights abuses. In Afrin and in the Turkish-controlled area from Tel Abyad to Ras al-Ayn, the future need not have been Assad or Turkey—there, Ankara’s actions are a net-negative. In Idlib and in parts of northern Aleppo known as the Euphrates Shield zone (ESZ), Turkey has improved the situation. Conditions in the Turkish areas therefore raise complicated questions about core humanitarian principles. Overall, as a fait accompli, Turkey’s continued presence likely offers better humanitarian conditions and basic security for residents than would the likely alternative of Assad’s return. This reality argues for international humanitarian and stabilization support to these areas, without acquiescence to a permanent Turkish occupation. But the humanitarian considerations are not clear-cut. Working with the de facto Turkish authorities in these areas could help innocent civilians but also requires humanitarian actors to subject their activities and aid delivery to Ankara’s politicized parameters and, at a basic level, legitimizes Turkey’s seizure of these areas and its effective expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Kurds. This reality requires strict conditional engagement, and the conditions under which engagement in the Turkish-controlled zones could make moral and political sense are a throughline of this study.

This report is based on extensive primary and secondary source research as well as interviews and conversations with nearly 60 experts, current and former officials, and Syrians knowledgeable on its subject. It examines the connections between the security situation in northern Syria and the refugee and humanitarian crisis, particularly as it plays out in Turkey and adjacent areas; while these challenges are often conceptualized separately and are addressed by different policy communities with differing priorities, they are inextricably linked in northern Syria. In a direct sense, further displacement and refugee outflows will be driven by military developments. Security dynamics will likewise determine humanitarian access, the limits of stabilization activities, and the likelihood of significant resettlement or further displacement in northern Syria. The report examines the interests of the key outside actors before proceeding geographically to consider the humanitarian and security conditions in each of five zones outside the Assad regime’s control—Idlib, Afrin, the Euphrates Shield zone, the Tel Abyad to Ras al-Ayn salient, and the SDF-controlled east—as well as how those security conditions could affect further population movements. The report then discusses some external factors influencing this picture: developments in Turkey, including perceptions of and among the Syrian refugees in Turkey; the border regime; and the U.N. cross-border aid mechanism. Finally, the report offers recommendations for greater U.S., EU, and Turkish engagement on this complex problem and points to some areas of possible—if fraught—cooperation.

Building upon previous proposals2 from the Center for American Progress, these recommendations focus on four broad goals:

Preventing a new stage of the conflict

Ensuring adequate humanitarian assistance

Exploring conditional engagement options with Turkey

Addressing external refugee issues

The full report is at this link

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/