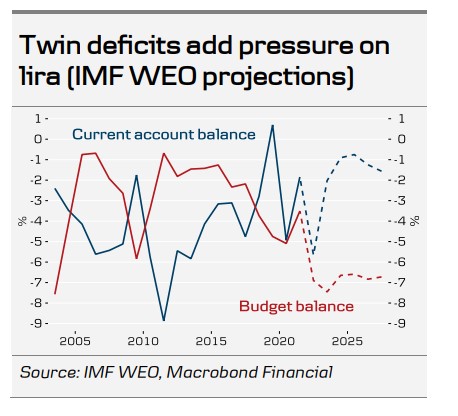

Highlight from the report: Despite a number of market-distorting measures in place, we think twin deficits and global financial tightening could push USD/TRY towards 25 in 12M. Yet, as long as an acute financial crisis can be avoided, the move is likely to be gradual.

CBRT swims against the tide

As major central banks across the globe rush to hike rates in an effort to tame record high inflation, Turkey’s CBRT continues to swim against the tide. After staying put for eight months, the CBRT surprised the markets with a 100bp cut in August. Since September last year, the central bank has cut the policy rate by 600bps to 13% despite inflation approaching 80% in July (and producer price inflation reaching 144%).

Undoubtedly under political pressure, the CBRT continues to prioritise growth and employment over price stability. Their strategy is faltering, since analyst consensus foresees GDP growth only at around 3-4% in the coming years, which is modest, compared to annual growth rates in 2010s sometimes exceeding 7%. Q2 growth was strong driven by substantial credit expansion, but economic activity has slowed down lately and employment growth stalled in June. Manufacturing PMI entered contractionary territory in March and business confidence remains near post-pandemic lows. Consumer confidence recovered over summer but remains well below its historical average.

Erdoganomics fails at multiple fronts

Apart from its failure to boost growth, Erdoganomics is falling short of achieving any meaningful improvement in current account dynamics. On the contrary, consensus expects a sharp decline (Editor’s correction: sharp increase) in CA deficit this year. Deterioration in terms of trade (higher energy prices, in particular) is largely to blame, but exports growth has also slowed down markedly from last year.

WATCH: Turkish Economy Won’t Survive The Winter

Investor exodus is another factor weighing on current account balance: in Turkey’s case, a decade-long process that started in 2012-13. During that period, the combined lira-denominated equity and government debt stock held by non-residents has been reduced to a fraction of what it used to be (20% for equities and 2% for bonds). ‘Erdoganomics’ has encouraged more non-resident selling, and in mid-August, foreign ownership was USD 12bn lower than a year ago. Yet, debt markets have absorbed most of the outflows, and in total, foreigners still hold USD 19.5bn of lira-denominated assets.

Recently, Turkish stocks have actually managed to attract inflows but it is difficult to see how this momentum could go on. On the contrary, further tightening of global financial conditions could well trigger more capital outflows from EM economies with substantial external vulnerabilities, and Turkey is particularly exposed.

FX protection scheme backloads risks

Since December 2021, the government’s FX protection scheme for lira-denominated deposits has successfully prevented a collapse in the exchange rate, but not without a cost. During March-July, the compensation scheme added TRY 60.6bn to government’s budget deficit (equivalent to 0.5% of full year GDP). Since June, the outstanding amount on FX-protected lira deposits has increased by an average USD 4bn a month. Assuming this pace continues and lira continues to depreciate (with USD/TRY ending the year in the 20-25 range), the additional strain on budget could be in the range of TRY 30-90bn for the rest of the year (equivalent to an additional 0.3-0.8% of GDP).

Rising and persistent budget deficits imply a growing sovereign debt burden

Bond repayments for the rest of the year amount to USD 7bn but taking into account the growing budget deficit, government financing needs could accumulate to anywhere between USD 8.5-12bn. In absolute terms and in relative comparison, Turkey’s total debt remains moderate at around 45% of GDP but the problem lies in the debt dynamics. The country’s foreign debt has tripled in the last 15 years and around 1/3 of it is short-term.

Most of the foreign debt lies with the private sector although the share of general government has increased in the last 10 years. Private sector debt dynamics have also changed in the sense that banks acquired a lot of foreign funding in 2010-2015 but have deleveraged since. Meanwhile, corporate borrowing from abroad has continued to increase, and almost the entire external loan stock is in hard currency.

Private sector as a total has substantial long-term external debt repayments looming in Q4, and the corporate sector alone has USD 1-2bn monthly repayments. We think the combination of global financial tightening, rising budget deficits and substantial refinancing needs at the private sector in the context of already-tight FX liquidity could push USD/TRY to 25 in the next 12M.

Indeed, debt repayments combined with a persistent trade deficit will drain Turkey’s foreign reserves, which remain at a low level. This is despite a recent boost that lifted net reserves (excluding central bank swap arrangements) from less than USD 7bn in July to 13.9bn in August. There have been speculations that the increase in reserves was due to an infrastructure project financed by Rosatom, and hence, that the money was transferred from Russia, but Turkish officials have not confirmed this information.

And—the geo-politics of current account

Regardless of whether the story holds or not, it raises interesting questions because, indisputably, Turkey plays a role in the ongoing geopolitical tensions. President Erdogan has been a vocal opponent of Finland and Sweden joining NATO. At the same time, he has presented himself as a peace-mediating neutral player between the West and the East, e.g. facilitating the deal that enabled the resumption of crops transportation via Black Sea.

WATCH: Can The Opposition Rescue Turkish Economy

As tensions keep building and the world sets into a new order in the aftermath of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, Turkey is likely to raise its profile and maintain an opportunistic approach. A successful balancing between the two blocs could well allow Turkey to benefit from the repatriation efforts by European businesses in longer term, assuming it gets its economy back on the rails. However, having your foot in two camps is risky. If EU-Turkey relations were being jeopardized, both sides would lose. The EU is by far Turkey’s largest import and export partner, as well as its main source of investments.

In strictly economic terms, Turkey needs the EU more than the EU needs Turkey, yet, politically, Turkey has leverage over Europe. It has the third most powerful military in Europe after France and UK. It controls the Bosphorus strait that connects Europe to Asia, and since 2016, the EU-Turkey migration deal has effectively prevented new migration waves to Europe. Stakes are high on both sides, and Erdogan has a few aces in his sleeve.

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/