Residents and officials say Erzin suffered no deaths and saw no buildings collapse, and they credit a long-standing policy not to allow construction that violated the country’s codes.

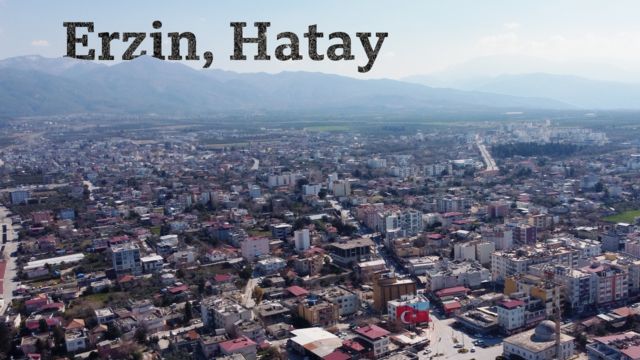

But this tiny city in Turkey’s southern Hatay province is an oasis of safety and normality while life throughout the region has been overturned by last week’s earthquake.

Residents and officials say Erzin suffered no deaths and saw no buildings collapse in the powerful temblor, and they credit a long-standing determination not to allow construction that violated the country’s codes.

Beyaz Yalcin was one of the lucky ones.

She was in Erzin with her four young children when the quake struck, rather than at home in nearby Gaziantep.

Yalcin, 33, has not returned home. She doesn’t know if her house is still standing or if, like so many in Gaziantep and throughout the region, it has been reduced to rubble.

“I am in shock. I don’t want to face the same situation again,” she said.

Yalcin is not the only one staying in this town out of fear.

Emre Tibikoglu, 39, who has been working for the municipality for six years, said he believed 20,000 people had flocked to Erzin since the earthquake, about a 50% increase in the town’s population.

“We know we are in an earthquake area,” he said, citing the insistence of the current mayor and previous ones not to allow buildings that failed to meet construction codes to be put up.

Tibikoglu said that whenever officials realized there were buildings that had been illegally built, they would get them taken down.

“Some local people were really mad about it,” he said of the residents living in those buildings. But he said the mayor held firm, knowing that a major earthquake could come one day.

Tibikoglu said he was not sure why other municipalities did not do the same, but suspected there could have been connections between local politicians and contractors, and said more stringent government regulations could have limited such a large-scale tragedy.

He said there are also no high-rise buildings in Erzin, decreasing the risks, though he said that he had heard some buildings in the town were damaged to the point that it was unsafe for people to remain there. The town may have escaped the devastation of the neighboring areas, but the 7.8-magnitude quake was felt nonetheless.

Engineers in Turkey had been raising fears over poorly constructed buildings for years, given the country’s vulnerability to huge earthquakes. Concerns only grew after a 2018 law provided amnesty for buildings with illegal construction, allowing them to be used as long as the owners paid a fine to the state.

The government has vowed a thorough investigation and ordered the detention of more than 100 people over collapsed buildings, though opposition groups have accused President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of failing to ensure that regulations were properly enforced while anger has grown over the issue.

Erzin is about 70 miles or so from the quake’s epicenter.

In cities farther from the center, as well as those close by like Osmaniye, just 12 miles away from Erzin, homes have been reduced to rubble and those who survived are still struggling to get aid.

Some have left for Erzin, seeking shelter with relatives.

Mountains and hills surround Erzin, something that locals believe has protected them.

But signs of the earthquake are there, on the damaged minarets and the debris scattered across the floor of the bus station, which has been cordoned off.

Life has otherwise largely gone on for residents, with locals dining in restaurants and shops remaining open, while police in the center of town are focused on directing traffic at the roundabout rather than in search-and-rescue operations.

With its roads intact and given its proximity to more gravely affected areas, Erzin has become a collection point for donations, such as food and clothing, according to Tibikoglu, who was overseeing efforts at one donation center this week.

She said her family had come to Erzin, where they have relatives, for a wedding before the quake happened. Though physically unscathed, she said, it had woken her children and left them scared — as well as lacking warm clothes and reliable shelter.

Her youngest child, 5-year-old Yahit, was standing in the cold wearing slippers and no socks, a green jacket and pants with a hole in them, while his siblings waited back in their temporary home with relatives.

Yalcin said she was sure there would be socks there for him but that she was also looking for blankets. Her top concern, though, was finding safe housing — perhaps a tent, since the building they were staying in had been damaged and she did not feel it was safe.

“We don’t have anything,” she said

Closer to the center of the town, Sultan Ergen sat with her husband and her sister on her mother’s porch.

They do not normally live together, but the siblings fled to their mother’s home in Erzin for safety after the quake. Ergen made the journey from Osmaniye along with her two children and her husband last Monday.

She said she knew the town was safer because it had also suffered less impact in previous, smaller earthquakes in the area, which is close to one of Turkey’s fault lines.

Ergen’s mother said that people in the town remained indoors after the quake because they trusted the construction of their homes.

“We don’t have a plan right now,” said Ergen, explaining that her family may never return to their home in Osmaniye. Her cousin was one of the many people killed in a luxury building in nearby Antakya, she said, one of the most high-profile sites to collapse.

As the fallout stokes recriminations across the country, families such as Ergen’s and Yalcin’s were navigating their temporary new lives in the town that was still standing.

“We don’t know how long we’re going to stay,” Ergen said. “Our building is really damaged.”

Kristina Jovanovski

nbcnews.com