THIS ONLY AN EXCERPT, republished because it has new value for Turkey

After a year in which he has not sold a drink, Istanbul bar owner Fuat Akyol is struggling to meet loan payments and save his 27-year-old business, which has closed its doors because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Small companies like Akyol’s have been the bedrock of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s political support — and some of the most vulnerable to pandemic restrictions and the country’s recent monetary policy zigzags.

Erdogan has made no secret of his loathing of high interest rates, and the roots of his antipathy may lie in part in the pain they heap on to heavily indebted small companies.

The rate rises hit many of the nation’s 3.2m small and medium-sized enterprises particularly hard. They are carrying debt totalling $107bn, or a quarter of all Turkey’s outstanding loans, and the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic has pushed many towards insolvency.

The government “sees cutting interest rates as the best means to increase resources for SMEs to retain their support”, said Oner Guncavdi, an economist at Istanbul Technical University.

Erdogan has also promised tax breaks for some of the nation’s smallest enterprises, known as esnaf, to help them weather the pandemic. But closed businesses like Akyol’s, which has no income to tax, are left out of the aid package, he said.

Esnaf are big employers, with 2m employing up to 20 workers each. More than 120,000 esnaf have filed for bankruptcy in the past year, according to the official registry. Many more have unofficially closed their doors but cannot afford to complete the legal process.

“There are scarcely any businesses without debt,” said Bendevi Palandoken, chair of the Turkey Tradesmen and Artisans Confederation, whose members employ one in eight Turks. “Tradespeople are the backbone of our economy . . . Their misfortune hits entire families, so when esnaf are in trouble, it directly impacts the wider economy.”

Tradespeople also underpin support for Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development party (AKP). “This is the AKP’s base,” said Guncavdi. “Esnaf in particular rely on credit to keep their businesses rolling over. Now they can’t find credit, or it’s too costly.” They also relied on credit-driven demand to sell their products, he said.

It is not just family-run shops and factories that are struggling. Tuncay Ozilhan of Turkey’s biggest business group Tusiad recently said in a rare, if veiled, critique that “the mixed signals” in policymaking made it tricky for industrialists to invest.

“All of us are trying to understand and assess the back-to-back, unexpected developments of the last few months and figure out the future. But how can decisions be made when the situation has become unclear and the parameters of authority and responsibility have become murky?” he said in a televised speech on Tuesday.

Loans to small businesses accounted for the largest segment of Turkish banks’ bad debt, said Lindsey Liddell, a senior director at Fitch Ratings in London. The ratio of all non-performing loans stands at 4.1 per cent.

WATCH: How Erdogan Killed the Turkish Economy in 10 Days?

These companies “are more susceptible to shocks for the simple reason that they have less cash buffers [and] generally run on low cash balances”, said Paolo Monaco of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s SME finance and development group, which advises and lends to Turkish businesses.

But previous boom-and-bust cycles had made them “extremely resilient” compared with western counterparts, he added.

WATCH: Should Turkey raise interest rates? Could she?

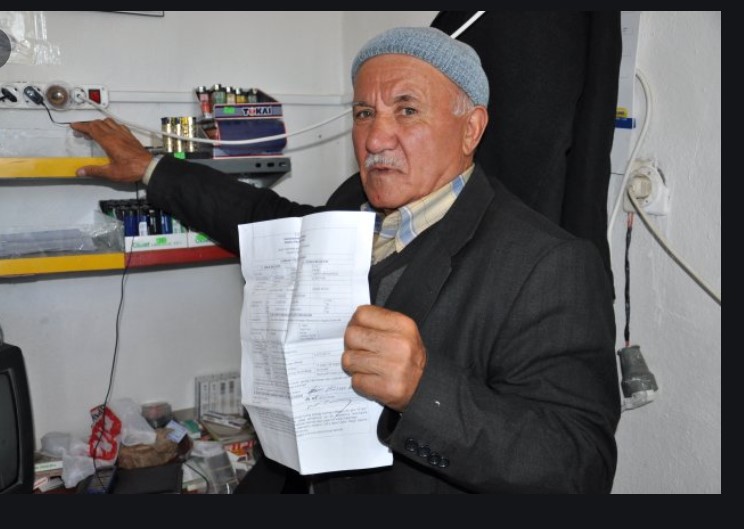

Akyol’s bar in Beyoglu, the central Istanbul district that is home to 350 bars and clubs, has weathered several crunches. Anti-government protests in 2013, an Islamic State bomb attack that killed four Israeli tourists in 2016 and a 2019 recession all drove customers away. “But I have never seen Beyoglu as deserted as now,” he said.

Before the pandemic, Akyol would earn enough to cover his monthly expenses on a couple of good nights.

Now his bar, called 45’lik, has been shut since March 2020, along with more than 14,000 other registered watering holes, and he is trying to pay back a TL500,000 ($63,000) loan to avoid bankruptcy.

He has almost depleted proceeds from the sale of his family’s plot of land and a one-time state grant. He has not paid rent in a year and faces eviction from the space he has occupied since 1994.

“The uncertainty has only gotten more intense. Banks that wouldn’t lend to us because we don’t have income now won’t even consider restructuring our loans,” he said.

Guncavdi warned that keeping interest rates low would “not be sustainable” because of rising inflation — running at close to 16 per cent — and “because Turkey can no longer attract overseas liquidity after the credibility of the central bank, as well as the government’s, has been hurt among international investors as well as the local business community”.

Akyol is unable to declare bankruptcy because he cannot pay severance and other liabilities, but he does not know if 45’lik will survive, especially with no sign that bars will open any time soon as cases of the virus rise again.

“There are two scenarios: We get wiped out or we get help,” he said. “That no one knows which one it will be is our biggest problem.”

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/