By Laura Pitel

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has hailed the recent period of calm in the Turkish lira as a sign that the economy is about to enter the “strongest period in the history of Turkey”.

That bold declaration comes after Erdogan, a staunch opponent of high interest rates, triggered a collapse in the currency at the end of last year when he ordered the central bank to aggressively cut borrowing costs despite soaring inflation.

Emergency measures — including a multibillion-dollar backdoor intervention by the central bank — have helped to restore calm in the currency markets. But inflation continues to climb, reaching almost 50 per cent in January, and it is unclear if the lira stability can last.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has hailed the recent period of calm in the Turkish lira as a sign that the economy is about to enter the “strongest period in the history of Turkey”.

That bold declaration comes after Erdogan, a staunch opponent of high interest rates, triggered a collapse in the currency at the end of last year when he ordered the central bank to aggressively cut borrowing costs despite soaring inflation.

Emergency measures — including a multibillion-dollar backdoor intervention by the central bank — have helped to restore calm in the currency markets. But inflation continues to climb, reaching almost 50 per cent in January, and it is unclear if the lira stability can last.

Here are five key things that must go Erdogan’s way if he is to keep the lira steady in the coming months.

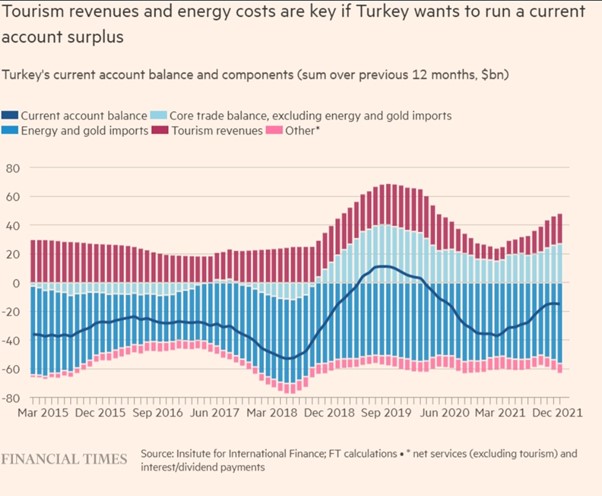

Can Turkey run a current account surplus?

Turkish authorities are gambling on turning the country’s chronic imbalance between exports and imports, which sucks foreign currency out of the country and puts pressure on the lira, into a surplus.

That requires limited consumer demand at home — something Erdogan may be unwilling to tolerate if he wants to pump up the economy ahead of elections. It also needs strong tourism revenues this summer and the avoidance of further escalation in tensions between Ukraine and Russia.

A conflict could cause a sharp rise in the price of energy, a key component of Turkey’s import bill.

Some analysts are sceptical, but Ugras Ulku, of the Washington-based Institute of International Finance, predicts that Turkey will run a $4bn surplus this year — compared with deficits of $15bn in 2021 and $36bn in 2020 — thanks to limited imports and booming exports and tourism. “We project that tourism revenues will recover fully to 2019 levels,” he said.

Will Turks stop putting their money in dollars?

At times of turmoil, Turks often prefer to keep their savings in accounts denominated in dollars, euros and precious metals — a phenomenon known as dollarisation that has been a source of pressure on the lira. At the end of last year, 64 per cent of all deposits in the banking system were in foreign currency or precious metals, according to central bank data.

That figure has fallen to 60 per cent after the launch of a savings scheme, unveiled in December, that promises to protect savers against exchange rate losses if they convert their dollar and euro holdings into lira. About $13.7bn out of foreign currency savings had been switched by February 14, according to data from the country’s banking regulator. That has helped to bolster the national currency and bring down total foreign currency deposits from about $264bn at the end of last year to about $251bn.

Will that trend continue if, as analysts expect, inflation tops 50 per cent in the months ahead and stays at that level for much of the year? “I’m expecting the volumes to grow, but for them to taper off over the coming months as inflation continues to be very high,” said Phoenix Kalen, global head of emerging markets research at the French bank Société Générale.

With average deposit rates standing at 17 per cent in mid-February, the value of savers’ money still faces severe erosion once inflation is taken into account. While the government predicts that inflation will fall to single digits next year, Kalen warns that there is a strong risk that the government will “grossly exceed its inflation forecast”

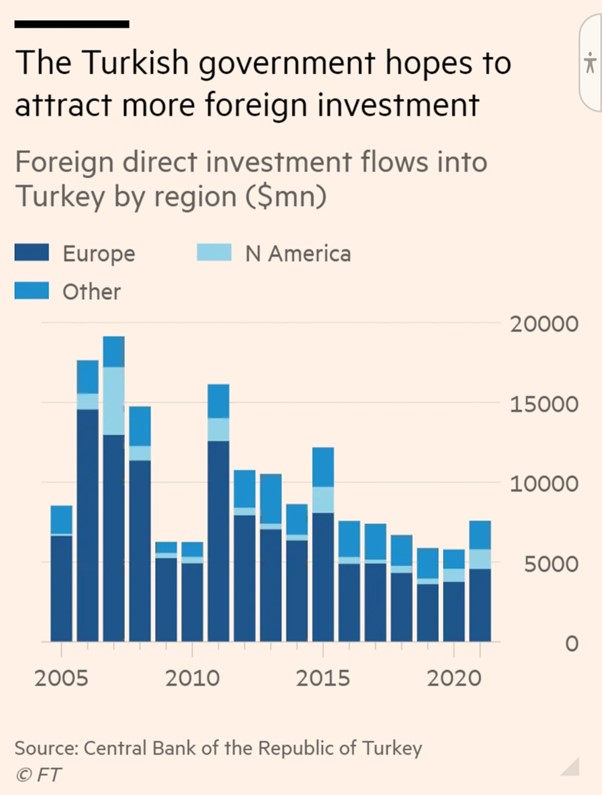

Will foreign investors come back to Turkey?

Erdogan argues that his “new economic model” will attract foreign direct investment that will bring hard currency into the country. Even with rock bottom valuations, western investors who have traditionally been the strongest source of FDI into Turkey remain hesitant due to concerns about the country’s economic management and the rule of law.

However, a recent diplomatic thaw with the United Arab Emirates came with a promise of a $10bn investment from the Gulf nation. Last month, the UAE struck a $5bn swap agreement with Turkey that bolstered the headline reserves of the country’s central bank.

Ankara hopes that a drive for détentes with other regional nations, including Saudi Arabia, Israel and Armenia, will provide a further boost to trade and investment. But GPW’s Coker warned that there had not been any sign of “frenzied dealmaking to buy up Turkish assets” as yet.

Will Turkish companies be able to roll over their debt?

Can the central bank keep intervening?

The rest of the article is here.