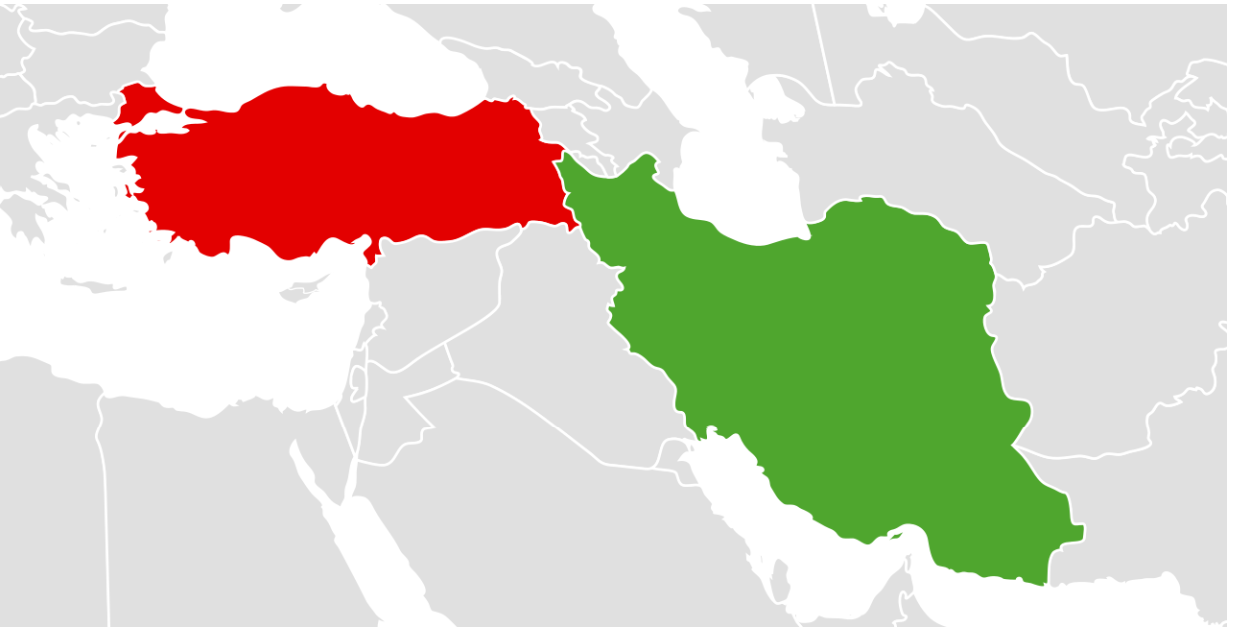

Turkey and Iran are strategically located between East and West, but they are land, not sea bridges. Besides, both countries face difficulties in terms of ensuring the security of the movement of goods or the functioning of their judiciary and the protection of citizens’ rights. All that translates into higher economic and political costs and risks. A median corridor that would cross not the Iranian or Turkish territories, but the Black and Caspian Seas, with maritime logistics links from Central Asia to the South Caucasus and Europe (Romania and Bulgaria), should be “cheaper”, both economically and politically.

Many years after the collapse of the regimes built on totalitarian ideologies, Iran continues to display totalitarian tendencies, subject to a religious nationalism that fits the logic of a conflict with made-up enemies. As a major exporter of oil and gas, Iran pays the cost of its own foreign policy subordinated to the ruling regime’s anti-Israel and anti-Western militancy. Tehran’s actions have destabilized the Middle East, thus attracting Western sanctions, which prevent the Iranian economy from fully accessing world markets. Instead of being included in regional and global cooperation schemes, Iran today is a pariah that preserves bitter, if not wholly aggressive attitudes towards most states in the area, with very few exceptions. Instead of being a bridge for East-West trade, Iran chose to be an obstacle that needs avoiding. Teheran continues to respond to its exclusion from key regional deals by stepping up its logistical and financial aid to the destabilizing actions of Hezbollah and Hamas to the west, as well as those of Shia Houthi rebels to the south, in Yemen, i.e. in strategic points for global trade.

And while the world evolves through commercial and intellectual exchanges, Iran continues on its path to nowhere, accompanied only by Putin’s Russia and, in very few cases, the much more cautious China. And the situation at home is rosy either. If the presidential election scheduled in the wake of the tragic death of president Raisi, does not produce a substantial change in Teheran’s decision-making, the regime and Ayatollah Khamenei, who is ill and is now 85, will face a resurge of tensions that have been grinding Iranian society for years. And Iran will remain an example of a global player with huge potential, but whose own politics prevent it from being part of the normal flow of regional and global exchanges. “Splendid isolation” will not help Iran progress, but could instead hasten the collapse of the very regime that endorsed this policy.

Another noteworthy important example for our discussion of global and especially East-West trade is that of Turkey. Its geographical position allows Turkey to play the role of a bridge between the East and the West, provided it actually owns up to the role instead of just mimicking it.

After decade-long conflicts in the South Caucasus, where Turkey has always openly supported Azerbaijan, Ankara today is faced with the opportunity of opting for cooperation. Turkey should convince Iran to jointly support the peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan. A lasting peace would create favorable conditions for Baku and Yerevan to cooperate with Georgia in order to ensure regional stability, a key prerequisite for attracting foreign investment.

Ankara’s interest in such a positive development is actually even greater than it may appear. Turkey has been looking for many years to open a logistics corridor to the Turkic states of Central Asia via Baku, but it has to get there either through Iran or Armenia. The political and economic costs would be lower, and even Turkey would stand to gain in the long term by cooperating with Armenia. Building a direct corridor crossing Armenian territory (the Zangezur corridor) from Turkey to the new Azeri port of Alat, on the Caspian seacoast, based on an agreement between Ankara, Yerevan and Baku would benefit not just Turkish exports to Central Asia, but also the development of Armenian and Azerbaijani economies. That means Turkey could become a long-term defender and beneficiary of stability and development throughout the South Caucasus, especially if cooperation agreements would include Georgia and Iran. Such an ambitious goal should guide Turkey’s regional policymaking if Ankara is determined to remain an active part of global trade.

By contrast, Ankara has, at least in recent years, opted for a rather conflictual approach, which is transparent in its skirmishes in Syria, Turkey’s tensions with Greece, the disputes regarding the gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Northern Cyprus dispute, its often blunt rhetoric towards its NATO partners and, last but not least, its support for Hamas, an organization hostile to two major players in the region: Israel and Egypt. Developments at home – an economic crisis, a regime with serious authoritarian tendencies, a judiciary suspected of being politically subordinated, an ongoing conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party – are just as unlikely to encourage investors.

Much like Iran, Turkey could lose the development race of its own doing.

veridica.ro