Toward great power status?

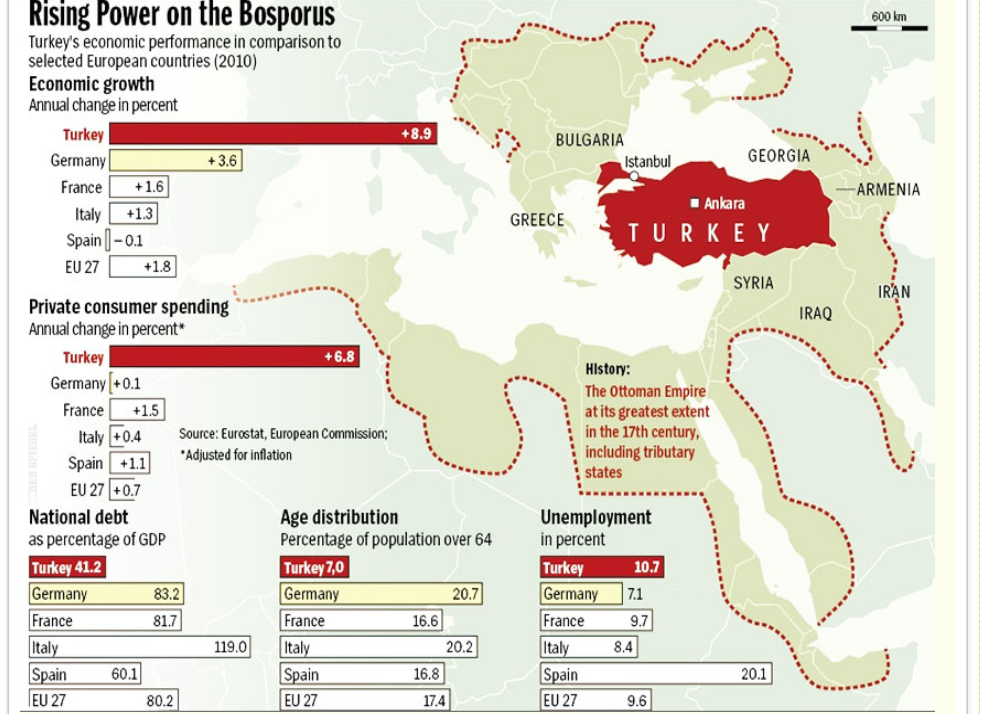

Nevertheless, it is pertinent to wonder if Turkey’s capabilities are going to be enough to reach great power status. Scrutinizing the various components of Turkish national power suggests that, even in the face of limits, Ankara has what it takes to advance its agenda or at least to try. Geopolitically speaking, throughout history the Anatolian peninsula has been a gateway for the projection of influence in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. When it comes to military matters, Turkey has a rather large army equipped with modern weaponry, as well as access to Western supplies thanks to its membership in NATO. Plus, Turkey has a national military-industrial complex which manufactures satellites and UAVs (note the optimal performance of the Bayraktar combat drone in operations of both regular warfare and counterterrorism). Remarkably, the Turks are also developing their own fifth-generation stealth fighter (the TAI TF-X project). Furthermore, with a GDP of over 692,380 million USD in 2021 (according to the IMF), Turkey is the world’s 23rd largest economy. Moreover, its population of around 85 million inhabitants makes it the 18th most populated country. Likewise, Turkey is arguably the only Muslim country whose universities are internationally competitive. In addition, the ethnic profile of Turkey and its common denominators and shared heritage with other Turkic peoples from countries located in the former Soviet Union is also an asset worth taking advantage of. Similarly, for historical and religious reasons, Ankara can become the leader of the Sunni world. Last but certainly not least, Turkey has a fairly competent and ruthless intelligence service.

On the other hand, the internal profile of the Turkish state has also undergone a profound redefinition. Under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (AKP), Turkey has become ‒ for all intents and purposes ‒ an unapologetically illiberal and authoritarian state. The regime established by Erdoğan and his closest allies does not even pretend to adhere to Western political and ideological standards anymore. In an open rejection of Kemalism and everything it stands for, the country has embraced militant Islamism as a framework to remake Turkish society, politics and cultural identity in accordance with a staunchly conservative worldview of what it means to be Turkish. To a certain extent, this has been fueled by external structural phenomena, such as the rising strength of illiberalism, the appeal of Caesarism as a way to deal with systemic crises, the resurge of religion as an instrument of socio-political control, and mobilization and the empowerment of nationalist forces in many places. Moreover, the 2016 attempt made by rogue military officials to launch a coup d’état against Erdoğan accelerated and deepened this process. It is unclear if the incident was masterminded by foreign entities (there are reasonable suspicions of CIA involvement and the fact that some rebel leaders had close connections with the US does not fully dissipate the existing doubts), a plot orchestrated mostly by internal rivals, or a complex combination of both. One way or another, it provided a good opportunity for Erdoğan to get rid of his domestic opponents and critics, as well as to carry out a purge specifically engineered to remove the remaining influence of Kemalism from the military and the security services. Thus, Erdoğan has consolidated his role as a strongman or, perhaps even more accurately, as the Sultan of a neo-Ottoman Turkey.

In hindsight, it looks like Turkey believes that Kemalism served its purpose but now that things have changed and Ankara is aiming higher, it is no longer deemed useful. Needless to say, this new socio-political reality has motivated overzealous Western liberals to demand the immediate expulsion of Turkey from NATO and other Western structures, but that does not seem very likely, unless an incendiary game changer takes place. Although the regime headed by Erdoğan has blatantly buried the previous commitment of the Turkish state to the project of Westernization, the pragmatic costs of alienating Turkey merely over abstract ideological preferences would exceed the potential benefits and could even push the Turks to embrace alternative geopolitical alignments with states openly interested in undermining the Western model of liberal world order.

Concluding remarks

Several geopolitical analysts have debated whether Turkey will side with the Western maritime powers or with the Eurasian behemoths in the context of Cold War 2.0. After all, both sides have offered convincing arguments but, far from being conclusive, the available empirical evidence is at best ambivalent. However, there is an alternative explanation that can be helpful to dissipate this ambiguity and reconcile seemingly contradictory signs. As a state that seeks to reassert itself, Turkey is only going to be aligned with its own national interests. For Ankara, there is no need to bandwagon confrontational coalitions as a junior partner, but it has demonstrated a strong political willingness to deal pragmatically on a win-win basis with major stakeholders without taking sides, a course of action that could hasten the emergence of Turkey as a major force to be reckoned with, regardless of which bloc ultimately prevails in the ongoing reconfiguration of the global order. In fact, said path to a certain extent mirrors the approach followed by other states with ambitious geopolitical aspirations (such as India) or regional powers that need to hedge their bets in an uncertain period of increasing upheaval, like Israel.

The Ottoman Empire is dead, long live the Ottoman Empire? Undeniably, it is pretty clear that the Turks are heavily invested in a pursuit of great power status and they have the potential to walk such a path. The proverbial die has been cast and this reality seemingly validates that sometimes geopolitical forces do drive the rhythmical resonance of behavioral patterns. However, there is no guarantee that their intended outcome will be achieved. They must deal with complicated internal challenges such as deepening economic hardship and financial turmoil. Likewise, foreign powers interested in altering Ankara’s strategic orientation might rely on covert action in order to destabilize Ankara, an active measure that could compromise Turkey’s ambitious plans through regime change, a color revolution, or the encouragement of domestic tensions. Externally, the rise of Turkey will definitely intensify strategic anxieties amongst neighboring states and it can eventually lead to a collision with mighty competitors if they think that the growing geopolitical projection of Turkey threatens their interests in areas in which the corresponding spheres of influence overlap. Furthermore, since Turkey is not self-sufficient in energy and raw materials, it will have to go to great lengths to secure access to such strategic resources. In a nutshell, the Turks are determined and capable of reaching a higher geopolitical position so that they can play a larger role in global affairs, but they still must overcome the treacherous influence of fortune and the vicissitudes of fate. History is not written in stone.

Editor’s Note: PATurkey is publishing only a small section of an in-depth analysis of Turkey’s post-Ottoman history and her geo-political future. The article is balanced and does an excellent job summarizing the salient efforts of Ataturk and his followers in propelling Turkey to Erdogan Era.

A must-read for those interested in recent Turkish history and her foreign policy priorities

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/