The global coronavirus pandemic threatens to send capital fleeing from emerging economies, as falling exports and a dearth of tourists cause foreign reserves to dry up. Meanwhile, weaker local currencies make servicing external debts harder.

This confluence of negative factors has financial markets watching closely to see if once fast-growing economies can weather a prolonged downturn.

Emerging economies are earning much less foreign currency this year. According to the International Monetary Fund, the average current account deficit of 141 emerging economies, excluding China, is expected to be 2% of gross domestic product.

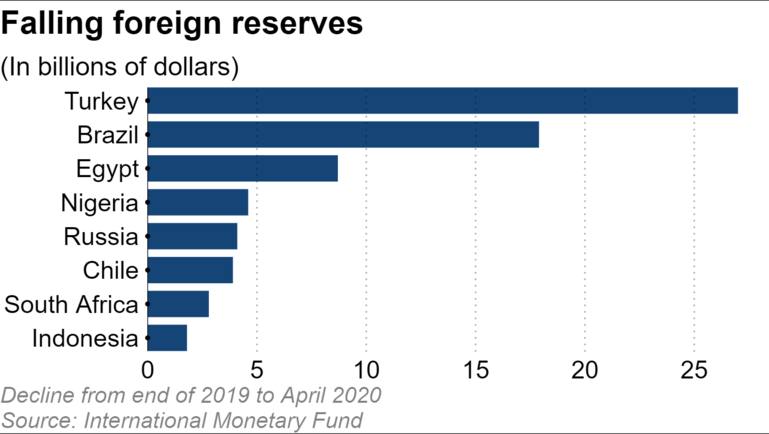

Foreign reserves, which offer a snapshot of a country’s ability to pay its debts, are dropping in emerging economies. About 60% of these reserves are in dollars. In 32 emerging economies, excluding China, foreign reserves fell by $50 billion in April versus the end of last year to $2.8 trillion.

That reverses a worldwide trend in recent years of climbing foreign reserves. Economic growth in emerging markets had pushed them up at a 10% annual clip, thanks to economic growth. But this year, on an annualized basis, the decline comes to $150 billion, the largest drop in the past two decades.

Out of the 32 countries surveyed, 20 saw reserves shrink, with Turkey experiencing the sharpest fall, at $27 billion. The Turkish central bank, struggling to defend the lira, has taken the unusual step of borrowing foreign currency from local banks. The country’s foreign reserves stand at about $50 billion, which is less than its short-term external debts and a level that is unsustainable.

Indonesia saw falls in its foreign reserves in February and March, as the central bank intervened in the market to stem the rupiah’s slide against the greenback. The prospect of running out of foreign currency, especially the dollar, prompted the government and the central bank to step in.

The shutdown of the tourism sector choked off a valuable source of foreign currency. Suharso Monoarfa, Indonesia’s minister for development planning, told a parliamentary hearing in late June that foreign exchange earnings from tourism would fall to between $3.3 billion and $4.9 billion this year, down from $19.7 billion in 2019.

Foreign investors are trickling back to Indonesia, easing pressure on the currency and foreign reserves, but with daily coronavirus infections still surging, there is a worry that the flow may reverse again.

In Egypt, the government is set to reopen 12 popular tourist destinations, including the pyramids of Giza. The tourism industry accounts for 11% of the country’s GDP. Due to the pandemic, foreign reserves have fallen by about 20% since March. With daily new coronavirus cases running at about 90% of their peak, the government is trying to reopen the economy.

In Brazil, oil and auto exports have plummeted. And China, a huge buyer of Brazilian soybeans and meat, has raised concerns over the country’s health safety measures.

Despite these problems, global financial markets have been relatively calm once the initial shock of the pandemic wore off, thanks to stimulus measures taken by governments and central banks. But should investors begin selling off emerging-market assets, the capital flight could be sudden. In the three months through mid-May, the currencies of Brazil, Turkey and South Africa lost about 30% of their value against the dollar, causing dollar-denominated debts to balloon.

At the same time, the safety nets provided by major economies and international organizations are fragile. The Fed has provided dollars through currency swaps to central banks, but among them only Brazil and Mexico count as emerging markets. Turkey is in talks with Washington for a swap, but the country’s strained ties with the U.S. make for slow progress.

The IMF has been criticized for lacking the speed and financial firepower to head off a crisis. The fund has roughly $1 trillion in lending capacity, but only half of that is available without the consent of big contributor nations. And to increase the size of the fund would require legislative approval in captial-providing countries, which is unlikely under the current circumstances.

If the support of international organizations and major economies falls short, problems in emerging economies may set off a global crisis.

By the end of 2021, $720 billion in loans will come due in 29 emerging economies, excluding China. Mizuho Research Institute predicts that if there is a debt crisis, European banks, which are the largest creditors to Turkey and Latin America, will be hurt. Japanese lenders would also likely suffer, as they hold roughly 20% of loans to South Africa, for example.

Excerpt only, visit link for full article

You can follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/