Turkey’s economy is in free fall, but this is unlikely to end the reign of Turkey’s pugnacious President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Sure, Turkey’s economy is on the rocks. Official sources put inflation at just over 21 percent. However, according to the Inflation Research Group, which claims itself independent, consumer prices have increased by over 58 percent over the past 12 months. According to research by the opposition’s Istanbul mayor, rent in the country’s largest city has increased by 71.6 per cent and food by a whopping 137 percent over the past year.

The broad unemployment rate stands, according to official figures, at 21.9 percent and the lira’s devaluation has been rapid.

To make matters worse, much of this could have been avoided had Mr Erdogan allowed the Central Bank to have independence and maintain its own interest rates. Instead, the president doubled down on his highly unconventional insistence that high interest rates lead to inflation.

WATCH: 2022 Predictions For Turkish Politics

Highlighting economic mismanagement, the opposition is demanding the government call snap elections. However, President Erdogan, who alone has the power to set a date, simply says no. So, he will stay put until mid 2023 at least.

And then what? Let’s look at the figures.

Even though Erdogan’s AKP is not as popular as it was a decade ago, a recent MetroPoll survey shows that it is still the most popular party with 34.3 percent support for the incumbents. While this represents a decrease of 8 percent since the 2018 elections, the main opposition party, the Republic People’s Party (CHP) hasn’t picked up any disenchanted voters. According to that same poll, the CHP would receive 22.6 percent of the popular vote. That’s the same as 2018.

Some AKP votes have gone to breakaway parties such as the former economy minister Ali Babacan’s DEVA or former foreign and prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu’s Future parties – 2.9 percent for DEVA while Davutoglu’s party’s support is too low to single out.

However, unless these breakaways join a parliamentary alliance, their votes will be lost as they will not pass Turkey’s high electoral threshold of 10 percent (or 7 percent if rumors that it will be lowered are true).

WATCH: Turkey Heading for Early Elections | Real Turkey

If they join the AKP-led People’s Alliance, the incumbents will effectively regain the lost votes, but if the breakaways enter the opposition’s Nation Alliance, it is possible that their supporters might see this as a step too far and go back ‘home’ to the AKP.

The AKP’s main concern is that the support of its coalition partner, the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), is waning, losing out to its secular nationalist rival, the Iyi (Good) Party.

However, the Iyi party’s polling results are not a sure thing. It polled well before the 2018 elections only to see lacklustre results. Also, the highly nationalist Iyi Party is at odds with the liberal and Kurdish oriented Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the third largest in the country, despite being under constant pressure and intimidation, at a time when all oppositional forces need to work together.

Any risk of parliamentary deadlock benefits the AKP. When, after the June 2015 general elections, the AKP failed to garner an overarching majority, and needed to form a coalition, the economy subsequently tanked. So, after a coalition government didn’t materialize and the election was rerun five months later, the AKP saw its vote share increase by almost 9 percent. In 2023 the AKP will again probably gain additional votes from those who reason that another five years of the AKP is better than political uncertainty.

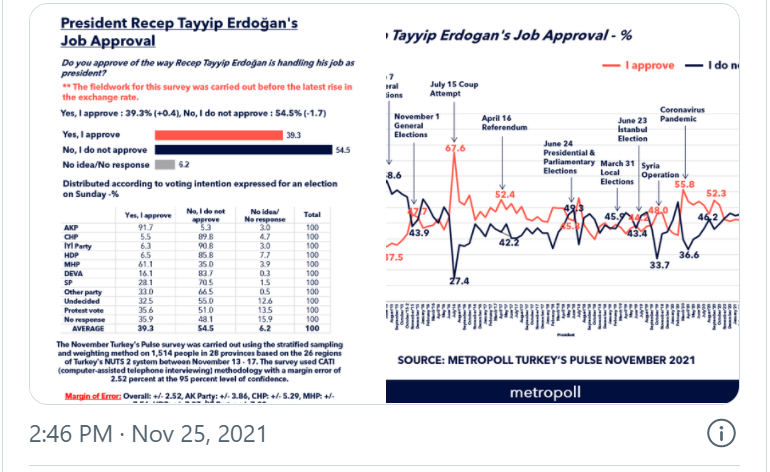

And then there’s the question of who will challenge Erdogan’s position as president, which by his hand has become by far the most powerful role in Turkish politics, with virtually unchecked power. It’s hard to get a solid grip on exactly how un/popular Erdogan is: the figures vary considerably depending on who does the polling.

Erdogan’s approval rating is just over 41 percent, according to the Metropoll survey conducted in September. This is hardly disastrous, considering that the economy is in tatters. Government commissioned polls indicate that 50 percent of the electorate would still vote for Erdogan.

The opposition haven’t mounted a challenger yet, but in order to defeat Erdogan, they need to find a rare unicorn: a unifying candidate who has secular, religious and Turkish national credentials but would also appeal to Kurdish voters, progressives and enough social conservatives to sway the balance.

Erdogan holds fast to the narrative that, since the founding of the republic, such groups were alienated and demonized by a western-oriented economic and political elite who spurned traditional values in defining who is a Turk. Many Turkish voters identify with this narrative and would be loathe to even consider voting for the opposition.

Moreover, after years of curtailing press freedom, most news outlets are slanted towards backing the government, and that has repercussions for how people vote. Such a narrow funnel of information obviously benefits the AKP, and can become a critical influence closer to elections.

Clearly, even journalistic puffery can’t disguise the hard bite of economic suffering. But for those readers who know they’re now struggling, and can see how prices are rising every time they go shopping, their daily news outlet offers them a form of reassurance: an overarching narrative of who’s to blame, mostly the “hoarders,” “speculators” and “usurers”: greedy retailer profiteers who stock up on goods, a shady conspiracy by international powers dedicated to keeping Turkey down.

Each year, tens of thousands of citizens are investigated for insulting Erdogan, making a grand total of over 128,000 criminal investigations over the last five years. That puts anyone campaigning trenchantly against his record in constant jeopardy, whether formal opposition parties or regular voters. When elections do take place in 2023, like in previous years, the government’s voice will dominate the airwaves and state resources will be used for the government’s campaign.

So, barring the possibility that the rumors that Erdogan’s ill-health are true (we’ve heard this before) and regardless of how bad the country’s economy gets, Erdogan and the AKP aren’t going anywhere – now, or in the near future.

Dr Simon A. Waldman is a visiting lecturer and research fellow at King’s College London. He is the co-author of “The New Turkey and Its Discontents” (Oxford University Press, 2017). Twitter: @simonwaldman1

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng