As the cycle of economic crises in Turkey began to shake the governing alliance, organised crime boss Sedat Peker has made a series of accusations about dirty relations within the state over the past month.

Such serious allegations from a fugitive mafia leader should be made the subject of an official parliamentary inquiry. However, it seems that the government is attempting to ignore them as it seeks to control a power struggle within the alliance.

As the day-to-day management of the economy leads to sharp fluctuations in Turkish asset prices and a cycle of economic woes, Peker’s videos, watched by millions in real time, will resonate on the electorate as the economic turmoil keeps unfolding.

So, it is worth focusing again on the realities of the economy, in particular on first quarter GDP data and leading indicators for growth in the second quarter of the year.

It was hardly a surprise when the government reported first quarter economic growth of 7 percent last week. In 2020, negative real interest rates, loan stimulus and monetary subsidies, along with the spending of an alleged $128 billion of the central bank’s foreign currency reserves, strengthened domestic demand to such an extent that the overheating economy will now take time to cool.

During lockdowns imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Turkey’s manufacturing sector was able to remain open and continue to increase its production and inventories. While the services sector was the most heavily hit, industry fed domestic demand, which was focused on commodity purchases. Then, with the discovery and distribution of the vaccine and the re-opening of the U.S. and EU economies, Turkish industrialists began to benefit from better external demand. During the pandemic period in the United States and the Eurozone, direct income subsidies to citizens provided savings increases. That growth in assets turned into consumption demand after the vaccines were introduced and the economies began to re-open.

The above are the main drivers behind the economic growth Turkey has achieved in the first quarter. That phenomenon is reflected in the share of capital in GDP increasing to 46 percent from 41 percent in the past three years.

But for households, the situation is not so bright. The government, which did not elect to create a larger budget deficit through direct income support, chose to stimulate the economy by encouraging household spending with cheap loans from state-run banks. The result of this choice was skyrocketing inflation rather than a budget shortfall, a wider current account deficit and a sharply depreciating lira. Some locals used the cheap loans to buy hard currency, while others mainly turned to the purchase of goods.

The interest rate hikes of November and December, implemented during central bank governor Naci Ağbal’s four-month tenure, reversed the decline in the lira’s value and led to increased consumer confidence. That prompted householders to keep on spending. As the government, or the ‘captain of the economy’, created debt, the share of labour in GDP dropped to 35 percent from 38 percent three years ago.

In short, while demand for Turkish goods abroad will continue to contribute to Turkey’s economic growth in the months ahead, domestic demand is set to weaken.

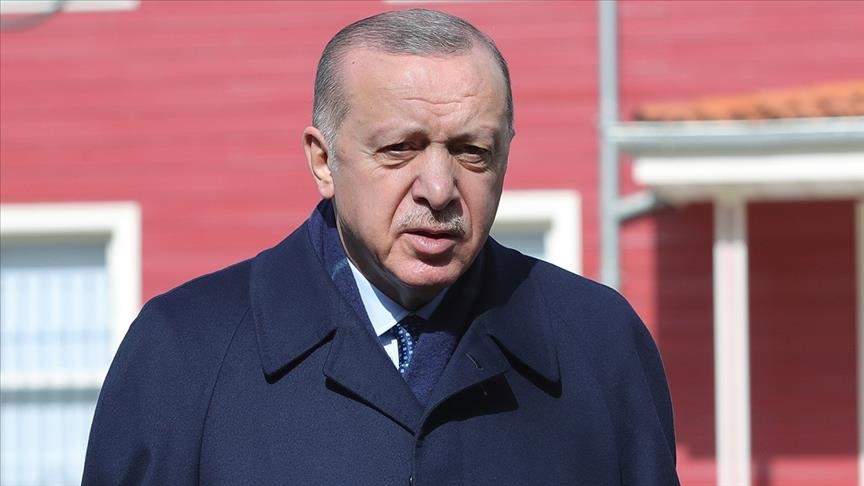

The question now, of course, is which way growth will go. Şahap Kavcıoğlu, the new central bank governor who President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan appointed in March to lower interest rates, is looking for an opportunity to fulfill his mandate. The question is how much further will the lira depreciate. Lack of trust in the government’s policies among foreign investors means the economy is being starved of capital inflows. Meanwhile, inflation is rising sharply in almost every country along the U.S.-EU-China axis, matching Turkey’s “booming” growth cycle.

Turkey’s purchasing managers’ index (PMI) is now sounding alarm bells for industry and the wider economy. Headline PMI dropped to 49.3 in May from 50.4 in April, falling below 50 for the first time in a year. The pandemic lockdowns are not solely to blame for the weakness. Any reading below 50 means contraction in the manufacturing sector. The pace of employment growth was at its slowest for the past 12 months, the survey showed. New orders from abroad have slowed down. Producers are reporting supply problems and rising costs and say they will reflect those costs in selling prices. The devaluation of the lira – it hit a record low last week – is providing a catalyst for this process. Another important factor is that producers are emphasising that orders from abroad, which have been increasing steadily over the last four months, are starting to slow down.

An index of consumer confidence for May published by BloombergHT television last week is indicating a decline in consumer demand. The Index hit an 11-year low last month, dropping 3.75 percent to 55.2. The survey also showed that consumers are spending today because they may be expecting more inflation and more currency depreciation tomorrow. Consumption demand is unlikely to continue at the same pace until the end of the year under current economic conditions.

While the base effect from last year will also elevate annual economic growth in the second quarter, loss of momentum in quarter-on-quarter growth appears inevitable. It is certain that Turkey will post economic growth of 5.5-6 percent this year, but the reasons will be mathematical rather than a reflection of solid, measurable improvement. Quarterly growth data is on track to close the year flat or negative, starting with the 1.7 percent posted for the first quarter. This means that economic growth next year may be around 3 percent.

The financial costs of the government’s choices in dealing with the pandemic mean that first quarter economic growth of 7 percent and expected full-year growth of 6.5 percent will not be felt by ordinary people. By 2022, the ‘captain of the economy’ will realise that it has become impossible to guide the ship back towards inclusive growth.

Monetary policy, which is controlled by the government, has failed to stem double-digit inflation and fiscal policies failed to provide income for citizens when they needed it most. Next, the government will be asking millions of people facing severe economic difficulties to vote in elections, scheduled, at the moment, for 2023. And the simple fact is that the senses of those same people have been sharpened by the accusations of Sedat Peker, who says top officials have been getting richer and richer at the expense of the man on the street.

Ahval News