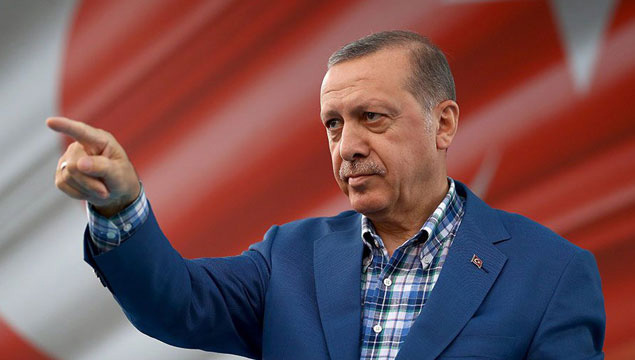

Turkey 2002: runaway inflation, high unemployment, huge public debt and corruption. In addition, a three-party coalition with the partners at loggerheads and resignations from within government ranks. Then the 77-year-old Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit fell ill. Back then, Turkey was in the throes of a severe economic and political crisis. New elections were called, and on 3 November the people rejected the established parties. Only two parties made it into parliament. The winner was the inexperienced AKP, the Justice and Development Party, founded only a year earlier, with its strong leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

From a standing start, it won an absolute majority on 3 November 2002, taking 363 out of 550 seats. The AKP has won all parliamentary elections in Turkey ever since.

Following his election victory that November evening, Erdogan said in a speech: “As Ataturk said: Rule is unconditionally for the people. After 3 November, a new era begins in Turkey. Today, inshallah, we are opening a new chapter. We are ready to take responsibility for leading Turkey into a brighter future.”

The AKP promised to respect the different ways of life of all citizens, to pursue a programme that would improve the work of constitutional institutions and to advance Turkey’s accession to the EU. There was initial talk of reforms, equality, justice and prosperity.

In the years that followed, the AKP did indeed manage a sustained economic upswing. By 2012, the hard-hit country’s gross domestic product had more than tripled. The AKP not only satisfied its voters, it also gained support from social democrats, intellectuals and Kurds. In the years that followed, the party created its own middle class and – by awarding state contracts – a super-rich elite that sustains it to this day.

By making various changes to the constitution, the AKP asserted itself against the influence of the military and the so-called established secular elite. Erdogan’s co-founder and friend, Abdullah Gul, was elected president. It was a watershed moment. Never before had an Islamic conservative politician with a headscarf-wearing wife held this post.

Yet in the second half of the AKP’s term in office, little remained of the initial promises of reform, strengthening democracy and modernising the country. From the Gezi protests in early summer 2013 onwards, the government became increasingly brutal.

Since the attempted coup on 15 July 2016, Erdogan and his AKP have only been concerned with retaining power. Legislation has been changed, Erdogan’s powers expanded and the status of parliament eroded. These days, Turkey is ruled by a regime in which the separation of powers lies in one hand: Erdogan’s. Police and prosecutors watch for a sign to take action against critics, artists, teachers, doctors, lawyers, journalists and students. Despite several corruption scandals involving top AKP politicians, their power remains unbroken. There is no prosecution with the courage to investigate them.

en.qantara.de