VOX: Emerging markets amid US and China cross-currents

politics-us-china

politics-us-china

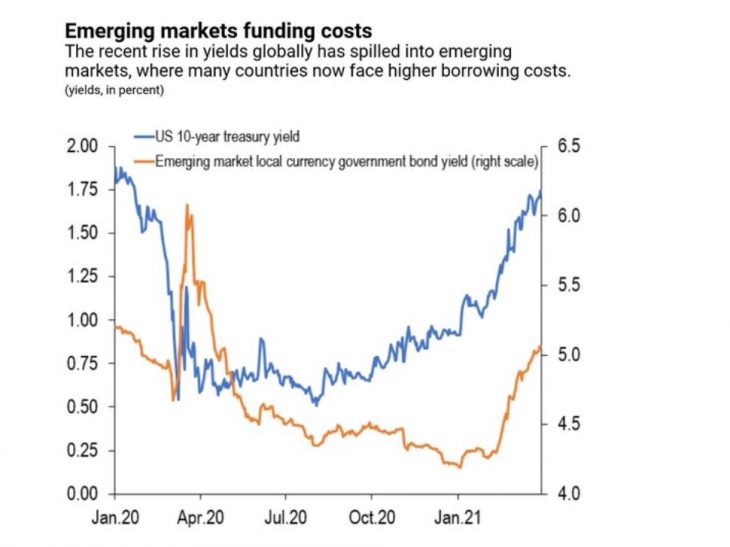

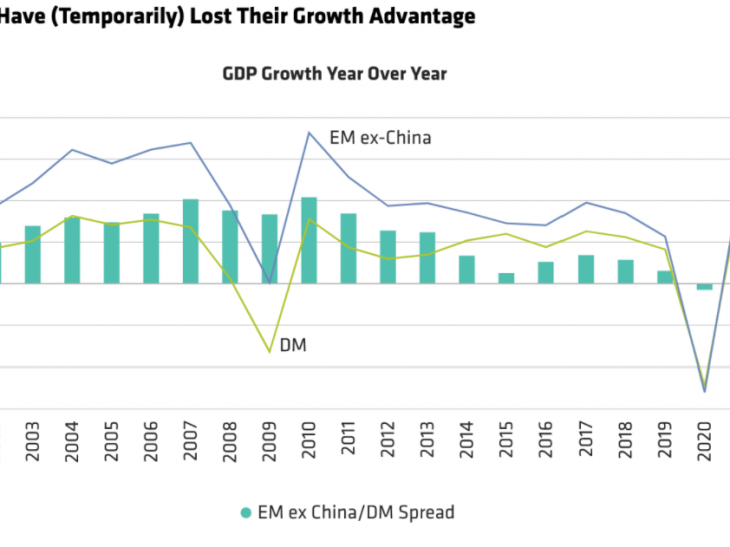

US fiscal policy should provide a large boost to the rest of world, but the US fiscal shock is not occurring in isolation. China is withdrawing policy support, reflecting official GDP’s return to its pre-COVID trend, while many other emerging markets are finding it increasingly difficult to continue with support measures enacted in 2020.

One reason many emerging markets are putting in place less supportive policy is that US fiscal policy has pushed up on US yields. This is a natural endogenous reaction to a brighter outlook in the US, but for emerging markets it risks being more akin to an exogenous tightening of financial conditions, unless the real economy spillover is sufficiently positive. A stronger external environment may also lead Chinese policymakers to tone back support.

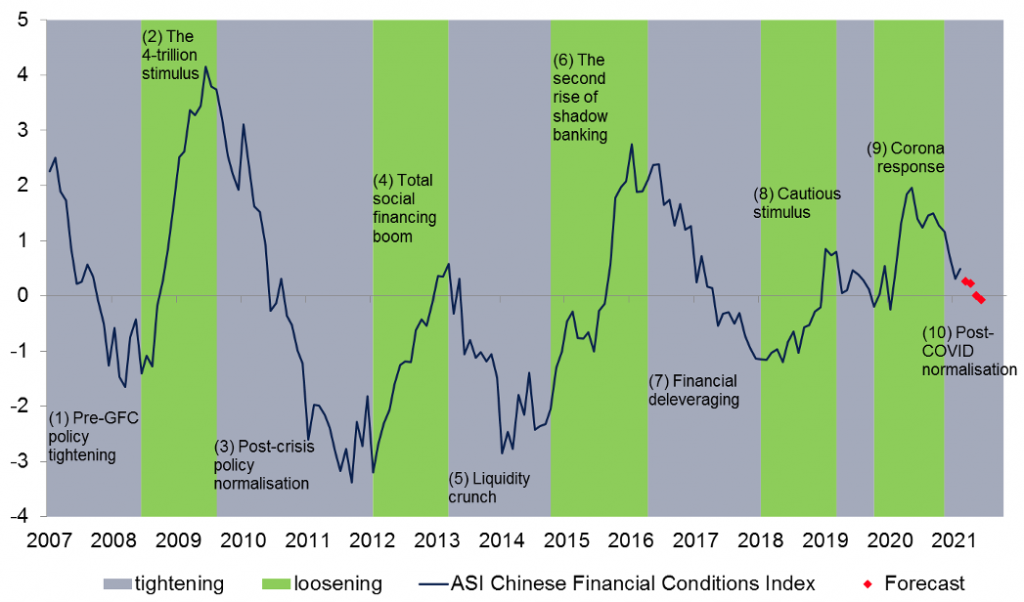

As we outlined in Gilhooly et al. (2020), Chinese financial conditions provide a useful gauge for assessing how conventional and unconventional policy levers are being operated. A financial conditions index (FCI) summarises not just the broad array of policy tools at the hands of the Peoples’ Bank of China (PBOC), but also other factors – such as bond yields, money, credit, risk premia, volatility, and FX – into an easily interpretable time series allowing for easy real-time tracking.

Figure 1 shows that the Chinese FCI has already unwound most of its previous loosening and we expect that it will break through the zero ‘neutral’ line soon. The credit impulse – a key component reflecting total social financing credit growth versus GDP – will mechanically turn negative as the last year’s shock to Q1 GDP drops out of the calculation. More generally, the authorities have been emphasising that while the PBOC’s main policy rates may not rise, fiscal support is being withdrawn and financial stability remains a key priority.

WATCH: Clash of Civilizations Reformatting World Economy

Figure 1 China’s financial cycle is rapidly swinging down and will turn slightly negative soon

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, Bloomberg, Haver as of February 2021

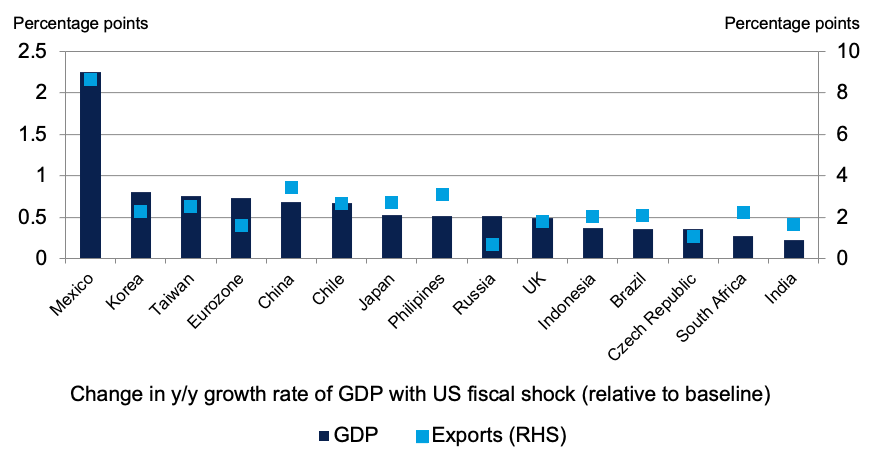

Considering how US fiscal policy might have affected global trade and major trading partners in more normal times provides a useful base to consider key differences in the current situation.

Using Oxford Economics’ global model, US fiscal stimulus akin to that announced since January would be expected to push up on US consumer spending and goods imports by $1,366 billion and $311 billion, respectively, increasing the current account deficit as a percentage of GDP by around 0.4%. Including second round effects via trading partners, this would be enough to raise world trade by 2.4% over a three-year period. For China and other emerging market exporters, US fiscal stimulus would normally push up notably on trade and GDP with the maximum response coming after one year (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Global models illustrate how a US fiscal shock could spill over in more standard backdrops

Source: Oxford Economics, Aberdeen Standard Investments as of March 2021

Aside from the fact that US fiscal policy is not being deployed in anything approaching ‘normal times’, the boost from the US to emerging markets in particular may be muted by China’s reaction. Using the Bayesian VAR (BVAR) framework developed in Watt et al. (2019), we have estimated the combined effects of the US growth shock and a tightening in financial conditions in China across several key metrics.

WATCH: World economy tour with Erda Gercek

Empirical results suggest that US fiscal policy could dominate the tightening in China, but this is not able to take account of some key features of the COVID shock.

There are good reasons to be cautious about the strength of the net boost implied by the BVAR.

First, there is a risk that Chinese financial conditions tighten more than in our central case. Past policy has been more cyclical than we currently assume, and it could be that the Chinese FCI fails to capture a decline in equilibrium interest rates. Given the commodities cycle is closely linked to the Chinese macroeconomic outlook, this may have ramifications for broader emerging market commodities exporters.

Second, and most crucially, the composition of both the US recovery and the fiscal package may mean that global trade – a key transmission channel – is unlikely to improve as much as you would normally expect given the loosening of US fiscal policy.

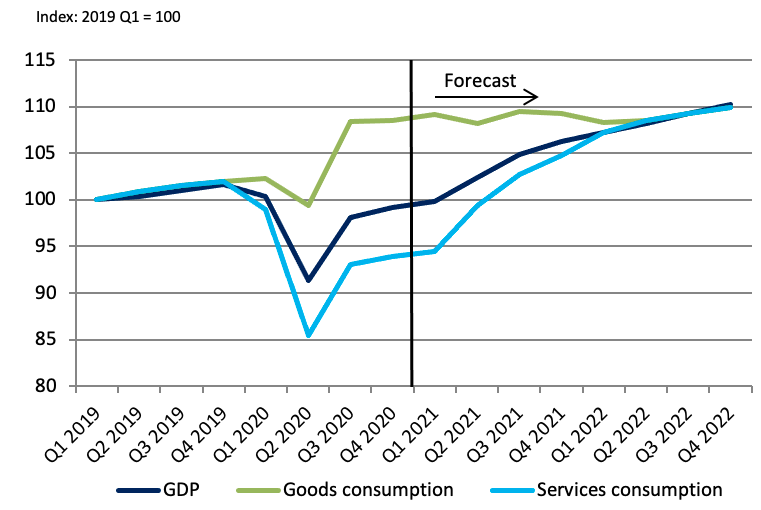

The COVID-19 shock induced a substantial rotation within consumption, pushing the share of real US goods consumption up by almost 4%. As activity normalises alongside vaccination – allowing further re-opening of the service sector – the share of goods consumption is likely to normalise also. Hence, when combined with the US fiscal boost, this means that US goods consumption may only flatline (Figure 4). Put another way, US fiscal policy may have stopped goods consumption falling, but it also suggests that it may generate little additional global trade (unlike the substantial impulse to global trade implied by the Oxford model in standard situations). A similar rotation is likely to occur in other developed markets, but without the offset from marked fiscal support, weighing on global trade.

Figure 4 The rotation in US consumption implies that goods consumption may flatline

Source: Haver, Aberdeen Standard Investments, as of March 2021

The composition of the US fiscal package also matters. The measures in the package passed in March are tilted towards individuals, suggesting a relatively low import intensity. The proposed American Jobs Plan is potentially more import-intensive, with spending focused on infrastructure, green initiatives, and research and development. The timing and magnitude remain uncertain, with spending spread over a much longer time frame (potentially ten years) and with some offset from tax hikes mitigating the economic boost.

Conclusion

No one doubts that the American Rescue Plan will provide a major boost to the US economy and this should dominate the withdrawal of policy stimulus from China. However, this positive shock will also occur alongside a marked shift in the composition of US and other developed market growth. The normalisation of goods consumption as vaccination allows a recovery in services has the potential to mute much of the benefits via global trade that would typically provide a substantial boost to emerging markets.

References

Baldwin, R, and B Weder di Mauro (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Chudik, A, K Mohaddes, M H Pesaran, M Raissi, and A Rebucci (2020) “Economic consequences of Covid-19: A counterfactual multi-country analysis”, VoxEU.org, 19th October.

Gilhooly, R, C Martinez, and A Watt (2020) “COVID-19: Putting the Chinese policy reaction into context”, VoxEU.org, 22nd June

Landau, J-P (2021) “Inflation and the Biden stimulus”, VoxEU.org, 8th February

Watt, A, C Martinez, J Lawson and R Fu (2019), “Decoding the Chinese financial cycle and its effects on the global economy and markets”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 14065.

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/