For Turks, the humble green plum (“erik” in Turkish) represents the start of spring. An intensely sour fruit, it’s available just once a year around April, when the plum tree bears fruit and they’re plucked before ripening.

For many decades, the sour plum was an affordable food item for the working class even if only as an annual treat. But rising prices and falling value of the Turkish lira in recent years have made this “harbinger of spring” and once-a-year delicacy absent from Turkish tables.

‘New economic model’

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been in power since 2002 — when he ran on a platform to combat hyperinflation that long plagued Turkey.

The early days of his Islamist-conservative Justice and Development Party (AK Party) government will be remembered for free market policies that helped rebuild the economy. But in recent years, Erdogan has pursued a tactic of lowering interest rates to keep inflation from rising — the reverse of the approach typically used by central banks.

“I cannot and will not stand on this path with those who defend interest rates,” Erdogan said.

‘Monetary policy is not functioning at all’

Erdogan’s words strike a chord with his conservative base, some of whom say the Quran approves of trade but considers debt with interest a sin. The belief is that only a select few benefit from interest rates, and not society as a whole.

Turkey’s economy is suffering as a result of that monetary policy, Arda Tunca, an independent economist and columnist at Turkish news site PolitikYol, told CNBC.

“Monetary policy is not functioning at all,” Tunca said. “Real income per capita has been wearing out in the past seven to eight years, and purchasing power is tremendously weakening. The most important point is that there is nothing done to prevent inflation from rising.”

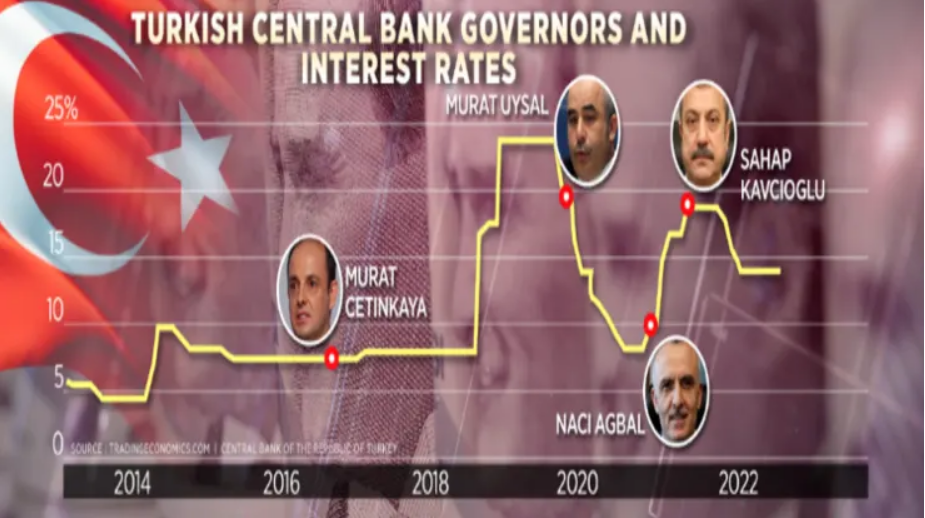

The president has pressured traditionally independent central bank governors to lower interest rates and removed those who resisted. The central bank began lowering rates in September from 19%, despite high inflation, which was then still below 20%. The rate now stands at 14%.

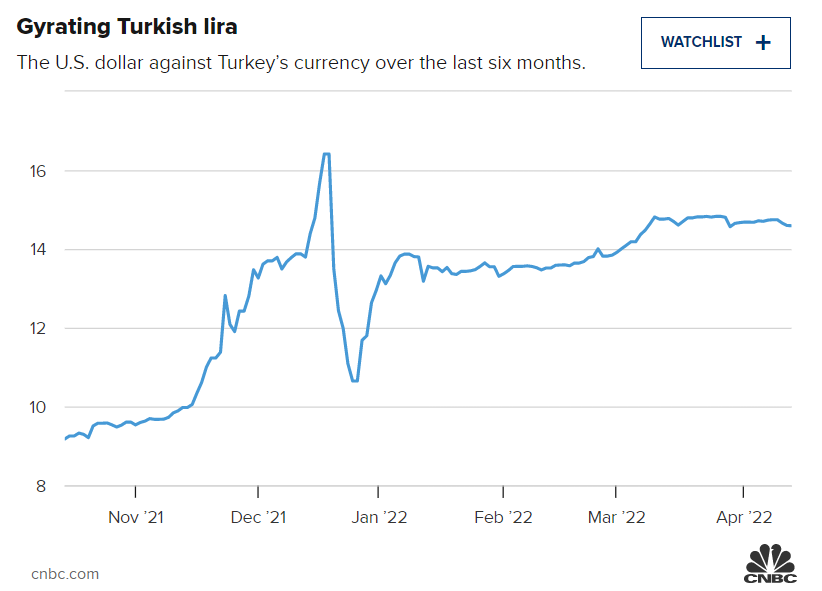

In the meantime, the lira has lost more than 60% of its value against the dollar in just six months.

Given that Turkey’s agriculture industry imports a range of items from seeds to fertilizers in dollars, the depreciation of the lira has translated to high food prices for households. Turkey’s CPI data for food and non-alcoholic beverages showed a rise of 70.3% year over year for March.

Turkey has fertile land for agriculture. But the country is dependent on agricultural imports.

“The incumbent government does not open the way to local manufacturers and producers to develop their capabilities in manufacturing and producing,” said Tunca.

No apparent plans to hike rates

Ahead of elections in 2023, AKP and its officials are digging in, with no apparent plans to raise interest rates.

Tunca said that while short-term changes can stem the bleeding for now, more will be needed: “Turkey has been in need of structural changes for decades. The only way to overhaul Turkey’s economic policies for the purpose of development is to configure a new set of policy tools which has the capability of modernizing the economy.”

In a recent speech, Erdogan conceded that the rise in global energy and food costs has hit Turkey — without mentioning any link to interest rates. He has instead indicated that the government will come down hard on those setting high prices.

“Turkey’s populace over the age of 40 experienced the severity of distortions on income equality. Yet, younger generations are witnessing such high levels for the first time,” Tunca said.

And so it seems that the tradition of eating green plums covered in salt may remain a distant memory for a big segment of Turkish society.

CNBC