As Turkey’s general election campaign enters its home stretch, a team of rivals is determined to dash Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s hopes of extending his rule into a third decade, argues Bobby Ghosh from Bloomberg Opinion, republished by Washington Post. On May 14, voters will in effect be choosing between an increasingly autocratic president and a quadrumvirate of opposition leaders dedicated not only to defeating the man but also to curbing the chief executive’s powers.

The main opposition candidate for the presidency is the Republican People’s Party leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu, a veteran pol conspicuously lacking in charisma. He is backed by three figures who have that quality in abundance: IYI Party chief Meral Aksener, and the popular mayors of Ankara and Istanbul, Mansur Yavas and Ekrem Imamoglu.

This collective represents the strongest challenge Erdogan has ever faced, and it comes as the president and his long-dominant AK Party are especially vulnerable. There is widespread dissatisfaction with the sorry state of the economy and anger over the government’s poor response to the twin earthquakes that devastated southeastern Turkey in early February.

Opinion polls have the opposition coalition, known as the Nation Alliance, leading the AKP-led People’s Alliance. Among those betting on the outcome, foreign investors and bond traders are showing signs of optimism that the Erdogan era may be about to close.

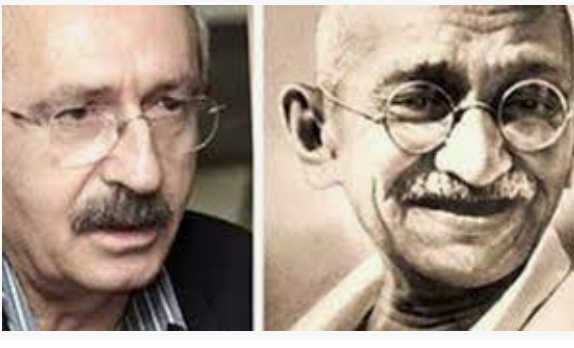

What would take its place? The only safe prediction is a change in tone at the top. Whereas Erdogan is famously combative, Kilicdaroglu has been likened to Mohandas Gandhi for being preternaturally calm — there’s even a slight physical resemblance.

But to keep his allies onside, Kilicdaroglu will require the leadership skills of another historic figure: Abraham Lincoln. Like the team of rivals marshalled by the American president during the Civil War, the four Turks are far from fast friends: Each has harbored hopes of becoming president.

Ironically, they are now collectively committed to weakening that office. Perhaps the most significant pledge in the opposition’s common platform is the return to a parliamentary form of government, reversing the switch to a presidential system that Erdogan achieved after a referendum in 2017.

It’s a promise they may not be able to keep. To change the constitution outright, Kilicdaroglu would have to win the presidency and the Nation Alliance a three-fifths majority in parliament. This is unlikely. A simple majority would suffice to call for a fresh referendum, but Erdogan and the AKP would fight it tooth and nail.

Still, were he to win the presidency Kilicdaroglu would be able to voluntarily give up some of the powers Erdogan has amassed and strengthen institutions he has emasculated. A good start would be restoring the independence of the central bank, which has in recent years come under increasing control from the presidential palace. Monetary policy has had to bend to Erdogan’s quixotic ideas about interest rates, leading to sky-high inflation, a plunging currency and a loss of investor confidence in the Turkish economy.

Over the past five years, foreign investors have pulled more than $60 billion from the bond and equity markets and slashed holdings of lira-denominated assets to the lowest level on record. Foreign holdings of lira bonds fell to $1.2 billion last month from $72 billion in 2013, according to data from the central bank. Foreign ownership of stocks is down to 29% from a historical average of 61%, according to official data.

An autonomous central bank is vital to thoroughgoing reform of the Turkish economy, which all the opposition parties recognize as necessary. “The current system is unsustainable,” Bilge Yilmaz, a finance professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and policy adviser to Aksener, told Bloomberg News. Yilmaz is expected to be given a top economic role if the opposition were to win.

Of course, not all the challenges awaiting Kilicdaroglu were he to become president would be of Erdogan’s making. Some would stem from the ambitions and agendas of his team of rivals.

The fours diverge on political ideology: Kilicdaroglu and Imamoglu are social democrats, Aksener is a nationalist and Yavas has moved from the latter camp to the former. Aksener, hailed by her supporters as “Asena,” or she-wolf, is a perennial flight risk: As recently as early March, she broke away from the quadrumvirate, only to be coaxed back by the others. The two mayors are likely to duke it out to succeed Kilicdaroglu as party leader.

If Kilicdaroglu does win, the other three are expected to become vice presidents — an unusual, unstable arrangement for any government. Managing them could be as difficult as undoing the legacy of his predecessor.

Excerpt only

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/