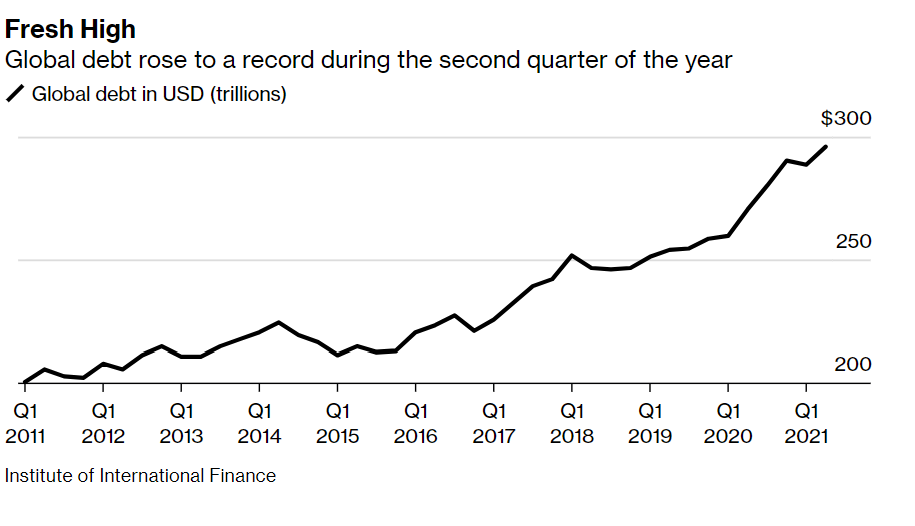

In last year’s COVID-19-induced global recession, global government debt surged in its largest single-year increase on record. Globally, government debt stood at a five-decade record of 97% of GDP and, in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), at a three-decade record of 63% of GDP in 2020. This comes on top of soaring private external debt, which often hits the public balance sheets in a crisis, not to mention considerable strains on EMDE banking systems.

How will this debt eventually be resolved?

EMDEs may find it tempting to rely on the post-pandemic growth and inflation rebound to reduce debt burdens. 2020). The global economy has rebounded from last years’ recession in the strongest recovery from any global recession in eight decades. This has been accompanied by a remarkably early and fast rebound in global inflation after an unusually muted decline during last year’s global recession.

But to what extent can EMDE policymakers rely on inflation and growth for reducing government debt burdens in a lasting manner? Our recent study (Kose et al. 2021a) sheds light on this question, as well as two others: What role can default play in returning debt to manageable levels? How can the global community help lessen debt burdens?

Inflation…

Unexpected inflation can erode real debt burdens if it raises nominal incomes faster than nominal interest rates. Inflation, typically combined with financial repression, has been credited with debt reduction in advanced economies after WWII and in Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s (Reinhart and Sbrancia 2015).

However, inflation has drawbacks as a debt reduction strategy, especially for EMDEs. First, the subsequent disinflation that would be needed to return to low and stable inflation would be economically costly.

Second, inflation is unlikely to reduce real debt burdens in a lasting manner when the share of short-term debt or foreign currency-denominated debt is large. In the median EMDE, foreign-currency denominated government debt accounted for 42% of government debt in 2019. If a large share of debt is short-term and needs to be rolled over, interest rates on newly issued debt will rise with inflation because investors demand higher interest rates in compensation. If a large share of debt is foreign currency-denominated, the depreciation that typically accompanies inflation raises debt service burdens.

Historically, in periods when EMDE debt service on external debt exceeds 22% of exports – a level EMDEs are now again approaching for the first time in three decades – the rate of debt default exceeded 20%. Challenges also arise when government debt is predominantly external as foreign creditors can more readily escape domestic financial repression.

Third, as high inflation becomes entrenched in expectations, it is reflected in nominal interest rates and no longer reduces the real value of debt. While financial repression may prevent a rise in interest rates to match inflation, it is a policy that distorts economic activity and is difficult to sustain after decades of open financial markets and capital accounts. As a result, surprise inflation would be most useful for a one-off reduction in high debt. If high debt is the result of persistent spending pressures or revenue weaknesses – as it has been over the past decade – a bout of surprise inflation cannot reduce real debt burdens in a lasting manner. Moreover, persistently high inflation risks undermining the hard-won credibility that some EMDE central banks have achieved over the past three decades (Ha et al. 2019).

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng