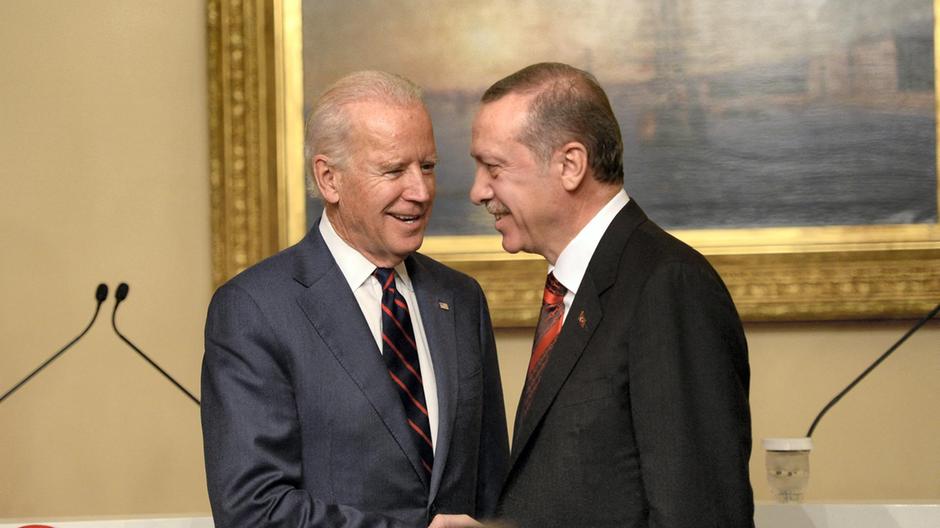

Joe Biden will depart on Thursday for Europe on his first foreign trip as US president, headed for an anxiously anticipated inaugural summit with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The last time the leaders of these two states met, in November 2019, feels like a lifetime ago. A few weeks prior, Ankara had launched a military assault on a mainly Kurdish area of northeast Syria days after the former US president Donald Trump vowed to destroy Turkey’s economy if Mr Erdogan went ahead with the invasion.

In light of his partial withdrawal of US troops, Mr Trump hoped to protect the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the lead fighting force in the US-led coalition to defeat ISIS. Ankara views the SDF as a branch of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is labelled a terrorist group by Turkey, the US and EU and has waged an insurgency in Turkey since the 1980s.

The Turkish assault went forward, pushing back the SDF while drawing international condemnation and accusations of war crimes on the part of Turkey-backed Syrian rebels. But Ankara’s most troubling move had come a few months before, when Turkey began receiving the S-400 missile systems it purchased from Russia despite repeated protestations from Nato allies and threats of sanctions from the US.

A group of lawmakers even urged Mr Trump to rescind his invitation, but Mr Erdogan was in the end welcomed to the White House. The US president left little doubt about his affection for the Turkish leader, as when he talked of the US’ strong ties to the Kurds. “By the way,” he added, gesturing towards Mr Erdogan. “I think the president has a great relationship with the Kurds. Many Kurds live currently in Turkey, and they’re happy and they’re taken care of.”

One pandemic and 19 months later, the Turkish president vowed last week to take care of the 12,000 mostly Kurdish residents of Iraq’s Makhmour refugee camp. Most fled there from Turkey in the 1990s, when violence with the PKK was at its peak. Ankara views the camp as a PKK incubator – an allegation that holds some truth – and Mr Erdogan threatened to extend Turkey’s ongoing military incursion deeper into Iraq and “cleanse” the camp.

Enter Joe Biden, who in a late 2019 interview with the New York Times called Turkey’s leader an “autocrat” and talked of emboldening Turkey’s opposition to force him out of office. Mr Erdogan adviser Ibrahim Kalin later said this analysis of Mr Biden’s stemmed from “pure ignorance, arrogance and hypocrisy.”

Things have improved little in the interim. Days after taking office, the Biden administration criticised Turkey’s imprisonment of political foes like Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtas and philanthropist Osman Kavala. In April, Mr Biden became the first US president in 40 years to recognise the Armenian genocide, upsetting Turkey, which refuses that label. He also waited three months after taking office to speak with Mr Erdogan on the phone, which many viewed as an intentional slight.

There are other roadblocks to friendly relations, such as the potentially massive fine against Turkey’s state-owned Halkbank for violating Iran sanctions and the US’ refusal to extradite Fethullah Gulen, a Turkish preacher Ankara blames for a failed 2016 coup. As previously detailed, Turkey-US ties are now largely defined by disagreements, yet few fear this constantly bickering couple will divorce.

Looking to lay the groundwork for a positive summit, US Ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield visited Turkey last week, met with Mr Kalin and reiterated Turkey’s standing as a reliable strategic partner and Nato ally before announcing nearly $240 million in new humanitarian aid for Syrians.

Mr Biden and Mr Erdogan will meet on the sidelines of the Nato summit in Brussels, and it is within the alliance, and on aiding Syrians, where they are likely to find common ground. Ankara thumbed its nose at the alliance last month, pushing Nato to mute its condemnation of Belarus and refrain from levying sanctions against Minsk for forcing the diversion of a Ryanair flight to detain a leading dissident.

Days later Mr Erdogan’s government offered a fig leaf, announcing it would send home the Russian missile experts overseeing S-400 installation in Turkey. The message is that Turkey has no plans to flip the switch on the Russian missile system, though it hopes to keep them on hand.

This may not be enough to appease the US, which sanctioned Turkey in December for its S-400 purchase, as required by its new National Defense Authorisation Act. “The updated NDAA language is ‘do not possess’,” Aaron Stein, research director of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, said in a tweet last week, referring to Turkey’s possession of S-400s. “This is the US position now. It’s not ‘We’ll talk in a working group’. Things look grim.”

This may mean Mr Biden will accept nothing less than Turkey destroying or dispatching the S-400s to a common ally, eliminating fears of Nato’s security apparatus operating alongside Russian-made systems. But however the S-400 situation plays out, Turkey and Nato have shown a willingness in recent days to join forces against common foes.

Last week, Turkey agreed to a $130 million deal with Nato to handle security at Kabul’s international airport following the upcoming departure of Western forces. The Taliban has never attacked Turkish targets, which underscores for Nato the value of a Muslim-majority member.

Also last week, Mr Kalin and Ms Thomas-Greenfield brokered a deal for the two countries to work together to ensure the uninterrupted delivery of aid to northern Syria. This is a clear stand against Russia, which has threatened to veto the UN Security Council’s expected reauthorisation of Idlib’s Bab Al Hawa border crossing next month.

Mr Biden is expected to raise the issue of Syrian aid and Bab Al Hawa when he meets Russian President Vladimir Putin on June 15, the day after his summit with Mr Erdogan. Ankara and Moscow have been on less than ideal terms of late, as seen by Mr Putin barring commercial flights to Turkey for six weeks in response to Turkish weapons sales to Ukraine.

There is room for greater Nato co-operation when it comes to Syria, and Syrians. Mr Biden has moved to prioritise humanitarian concerns in Syria, while the EU has for years relied on Turkey to provide aid and sanctuary to Syrian refugees and displaced people to keep them from streaming toward the EU border. Europe wants increasing stability in northern Syria, which can only be achieved via co-operation with the US, which maintains a military presence in the northeast and close ties to the SDF, and Turkey, with its occupied areas. Turkey’s incursions into Afrin and northeast Syria drew accusations of ethnic cleansing, as has its plan to resettle up to 2 million Syrian refugees in areas it controls.

Rest of the article is here.