When one brave soul from Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s ruling party decided to confront him about mounting public discontent over the economy, he was met with short shrift. “You are lying. I know the street better than you do,” Erdogan replied angrily, according to the Turkish president’s interlocutor, who remains a party member: “He is convinced that some in the party and in government are exaggerating the problems.”

Erdogan is facing growing warning signals that his idiosyncratic approach to running Turkey’s $765bn economy is not working. While economic growth looks good on paper, it has not translated into jobs. Inflation reached almost 20 per cent in September, and the currency is losing value. A decade ago it cost around 1.8 lira to buy a single dollar; today that figure is almost 10.

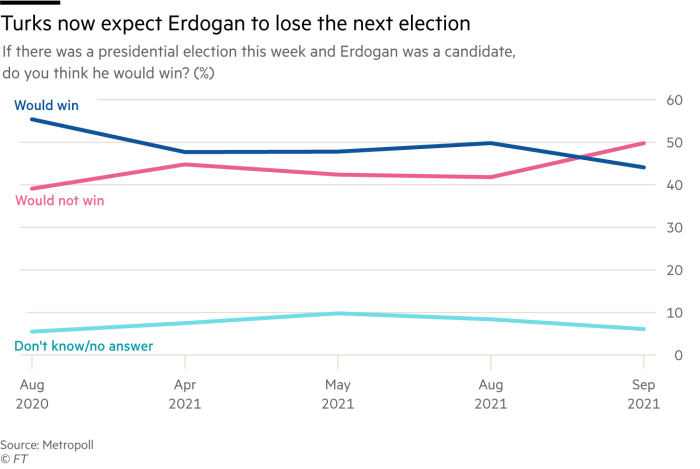

Most crucially for the president, who on Wednesday marks the 19th anniversary of his ascent to national power, support for his Justice and Development party (AKP) has fallen around 10 percentage points from parliamentary elections in 2018 to hit historic lows of between 30 and 33 per cent.

“The main and most important reason is the economy,” says Ozer Sencar, head of the polling company Metropoll. “Right now there is a large group of people who cannot meet their basic needs. About 30 per cent of the electorate cannot get by. This is the fundamental reason why people are leaving the AKP.”

Turkey’s opposition has never been so bullish. Even if others accuse them of wishful thinking, they are convinced that the failing economy is going to help them bring Erdogan down. The next round of elections is scheduled for 2023, the centenary of the founding of the modern Turkish republic, but some analysts predict that a snap vote could be held as early as the first half of next year.

“There is not long left,” Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the leader of the country’s opposition Republican People’s party (CHP), told the country in October. “Be patient. You might be hungry. Your electricity might get cut off. You might get arrested, thrown into prison and even tortured and strip-searched. But be patient. There is not long left.”

Yet the Turkish president, surrounded by sycophants and dogged by rumours about his health, appears either unable or unwilling to listen to those urging him to change course.

In October, he stunned the markets again when his central bank slashed interest rates amid soaring inflation, and at a time when central banks around the world are raising rates. The risky move triggered a fresh plunge in the lira, widely viewed as a barometer of the country’s economic health. Days later, he risked the worst diplomatic crisis in decades by ordering the expulsion of 10 western ambassadors who had called for the release of a jailed philanthropist, before backing down from the threat.

“Domestic policy, foreign policy, the economy, it’s all going from bad to worse, says one former minister who is unhappy with the direction of travel but has chosen to remain inside the AKP. “There is still a chance to turn the situation around, to change the atmosphere. But there’s only one man who can do that. It’s up to him.”

Erdogan’s critics say that is nonsense, arguing that the president has run out of energy, ideas and time. Upbeat opposition officials say there are already signs that the winds are changing. Bureaucrats are looking over their shoulder, they say, amid warnings from Kilicdaroglu that they will be held to account for decisions they make now. Prominent company bosses, including some notorious for their links to the AKP, have begun to make tentative approaches to the centre right IYI party, says Umit Ozlale, one of its vice-presidents. “Either they are hedging their political risk or they perfectly see that everything is going wrong and they are ready to show their support.”

‘Growth at any cost’

Though still a formidable politician, today Erdogan often looks tired and gaunt. The president momentarily appeared to fall asleep during a video message to party officials in July. Amid mounting rumours about the state of his health, his aides produced a video last month on social media showing the 67-year-old president, dressed in a baseball cap and fluorescent tabard, playing basketball.

Government officials say the president still draws energy from getting out on to the streets, but his encounters with the public have increasingly been marred by missteps. Last year, on a visit to the eastern city of Malatya, he told one voter who said he was struggling to feed his family that he was exaggerating. Over the summer he was widely mocked when, during a visit to a region ravaged by wildfires, he sought to console residents by tossing bags of tea from his presidential bus.

Ozlale, whose IYI party has been soaring in the polls and which could form a government with the CHP if the opposition were to win power, says the highly centralised executive presidency put in place by the Turkish leader three years ago is not capable of dealing with the country’s growing problems. “Erdogan is the only decision maker,” he says. “He does not have a good information network. He’s getting older, more tired.”

The president, who for years won elections on the back of ushering in greater prosperity for millions, continues to trumpet the country’s impressive headline growth figures. The IMF projects that Turkey’s gross domestic product will expand by 9 per cent this year — a rate that puts it ahead of China and just behind India. But even the country’s largest business association, Tusiad, which is often reticent about criticising Erdogan’s policies, has warned that the government’s obsessive focus on growth at any cost is damaging the country.

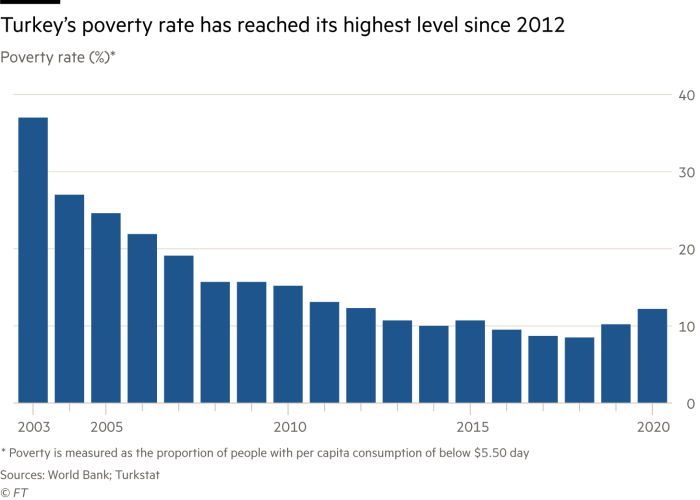

Wage growth has failed to keep pace with rampant inflation. Low-income households have been hit hardest by the accompanying decline in living standards. The poverty rate, which fell dramatically during the AKP’s first decade and a half in power, began to rise again in 2019 in the the aftermath of a severe currency crisis that triggered a recession and caused the loss of 1m jobs.

“This translated into nearly 1.5m additional poor, a total of 8.4m nationally, erasing almost all the gains achieved in the three years preceding the economic turmoil,” warned a World Bank report this year that predicted the trend would be exacerbated by the Covid pandemic.

Refet Gurkaynak, chair of the economics department at Ankara’s Bilkent University, says it feels “insulting” to the public to be told that the economy is booming against this backdrop. “In their daily lives they see unemployment, rampant inflation and eroding purchasing power and their lives are clearly not getting any better — in fact they’re being made much worse.” Despite this, Erdogan has relied on using cheap credit to stoke consumption and construction even as that model has caused chronic inflation and a weak currency and made the country poorer. New foreign direct investment stood at just $5.8bn last year, compared with a peak of more than $19bn in 2007.

Having consolidated his grip on Turkey’s institutions, Erdogan has clashed with the nominally independent central bank, repeatedly demanding and getting lower interest rates — which he believes, contrary to economic orthodoxy, help combat inflation. The combination of loose monetary policy and runaway price rises has caused the country to lurch through a succession of sharp currency depreciations.

International investors, whose money is needed to finance Turkey’s $450bn external debt burden, were briefly cheered last year when Erdogan in effect fired his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, after a disastrous two-year stint as finance minister. At the same time, they welcomed the appointment of Naci Agbal, a respected technocrat, to the helm of the central bank. But Agbal lasted just four months before he too was sacked by the president — the third firing of a central bank governor in less than two years. His successor, Sahap Kavcioglu, is a former state bank official who in September began cutting rates.

“It seems to be groundhog day,” says Joseph Mouawad, a portfolio manager at the asset manager Carmignac. “We keep having these cycles: the Turkish central bank hikes rates, Erdogan gets upset, changes the staff, they cut rates and then when it is really bad it changes again and they hike rates.”

Mouawad warns that, this time around, the experiment is “more dangerous” due to rising energy prices that will add to Turkey’s import bill and a shift towards rate hikes by global central banks that could divert capital from emerging markets. “You could end up with a low growth and high inflation-type situation, which is the worst of all worlds.”

Reluctance to speak the truth

Exasperated members of the government and the business community claim that Erdogan, who has sidelined internal critics, has a tenuous grasp of economics and is rarely challenged even by members of his own cabinet.

“The ministers tell us: ‘you need to talk to the president so that he understands the situation’,” says an executive at a major Turkish conglomerate. “But why should we? This is their job.”

Party insiders say some senior advisers in Erdogan’s entourage privately oppose his obsession with cutting rates but are unwilling to tell him. “The president doesn’t like strong people around him. Everyone knows that,” says one government official. “So no one is willing to speak the truth.”

Others believe that the president’s approach is more calculated than ignorant. Burak Bilgehan Ozpek, a political scientist at Ankara’s TOBB University, says low interest rates and a cheap currency benefit the network of cronies, especially those in the construction and tourism sectors, who have helped prop up Erdogan’s government.

He adds: “The correct term here is survival . . . He doesn’t want to have a dynamic economy, he doesn’t want to make the Turkish economy great but he wants an economy that is sufficient for him to win the next election.”

Ozpek is doubtful that the strategy will work in light of the opposition’s tactical shift away from identity politics based on religious, cultural and ethnic divides that alienated AKP supporters, and on to what they say is the ruling party’s inability to govern. Erdogan’s opponents are “raising questions about the ability of the AKP elite rather than its ideology and identity”, he says. “And this strategy is working under such economic conditions.”

While there is dismay within the AKP at the direction of travel, there is no obvious internal challenger to the Turkish president.

Albayrak, who is married to Erdogan’s daughter and was once seen as his chosen successor, has disappeared from public view. Suleyman Soylu, the charismatic and ambitious interior minister, was damaged by a series of recent corruption allegations made by an exiled mafia boss. Soylu denies the allegations. Despite everything, the brand of Erdogan — whose tough guy image and tub-thumping rhetoric still inspires a hardcore of supporters — remains, according to polling, more popular than that of the AKP itself.

How many autocrats step down?

Pls. find the rest of the article here.