Summer’s end arrived in Istanbul like a warm breeze last week. After a pandemic-driven sabbatical, the Orient Express pulled into town for the first time since 2019, welcomed to Bakirkoy Station by an Ottoman-style band after a five-day journey from Paris.

The celebration seemed fitting; the streets of Turkey’s financial and cultural capital have thronged with visitors in recent weeks, including French filmmaker Gerard Depardieu, who took in the views, and reportedly a good deal of seafood, at a well-known rooftop restaurant near Taksim Square.

Tourist arrivals to Istanbul exceeded pre-pandemic levels this summer, hitting a 10-year high and driving a 190 per cent surge in national tourist revenues. After years of complaints – that it’s too big, too far from the centre, and poorly run – Istanbul’s huge airport achieved its aim of becoming Europe’s busiest.

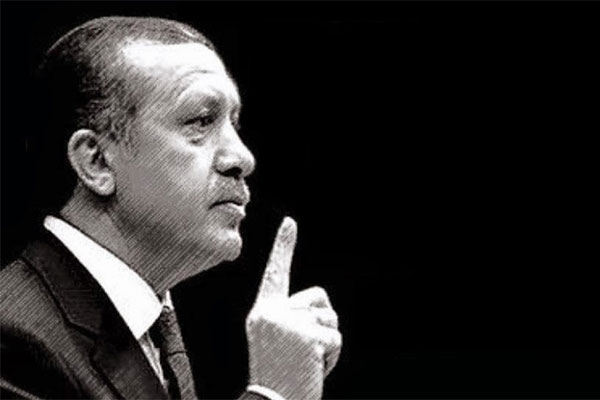

This helped drive Turkey’s economy to strong 7.6 per cent growth in the second quarter, besting forecasts and most peers. Buoyed by this growth, and diplomatic coups like the recent Russia-Ukraine grain deal, Turkey’s ruling AKP – which will mark 20 years in power in November – saw its polling numbers reverse a downward slide.

For the first time in months, backing for the AKP and its parliamentary partner the far-right MHP (at 35 per cent) topped support for the two main opposition parties, CHP and IYI (32 per cent). Further boosting confidence, reports from the frontlines in Ukraine had Turkey’s Bayraktar drones wiping out tens of millions’ worth of Russian hardware in a few days.

But there are signs of trouble ahead. A ship ferrying 3,000 tonnes of corn from Ukraine, thanks to the grain deal, ran aground in the Bosphorus on September 1, halting maritime traffic for hours and perhaps signalling a change in the weather. About 30 hours later, a cargo ship headed for Ukraine to pick up grain struggled with engine trouble in the same section of the Bosphorus, again halting traffic on the key regional shipping corridor.

On the weekend, reports emerged of troubling criminal activity. Istanbul police nabbed a terror suspect who they said had received training at a refugee camp near Athens run by the Kurdish militant PKK and supported by the Greek government – which, if accurate, would mark a troubling new collaboration.

Also, a top western news outlet reported that Ankara – which Kyiv has praised for barring the wartime passage of Russian naval vessels through the Turkish Straits – may be allowing Russia to transit weapons and armoured vehicles through the Bosphorus and into the Black Sea via Russian commercial vessels.

This is technically not a violation of the Montreux Convention as the ships are non-military, top Bosphorus watcher and maritime expert Yoruk Isik explained to The Wall Street Journal. But he added that if it had the political will, Turkey could make clear to Russia that such evasions were unacceptable. The fact that it had yet to do so suggests Ankara may have hoped to quietly aid Moscow.

It wouldn’t be the ruling party’s first attempt at sleight-of-hand. Turkish mafioso Sedat Peker became an online sensation last year with a series of viral videos detailing purported government corruption. In a 50-tweet thread under the Twitter handle “Crazy Sergeant”, he resumed his act last week and added to the air of foreboding with a series of new allegations involving advisers of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Former journalist-turned-politician Ahmet Sik, an opposition-party member of parliament for Istanbul who has written a book about corruption, said in an interview days later that Peker had highlighted hundreds of alleged crimes yet Turkey’s judiciary had taken no action. “The AKP will be shut down as a criminal organisation,” Sik predicted.

He may find a sympathetic ear among many Turkish citizens struggling to pay their bills and muddling through a seemingly endless economic crisis. Despite the economic expansion, inflation in Istanbul sits at nearly 100 per cent, above the national rate of about 80 per cent, and the lira hit 18.2 to the US dollar over the weekend, threatening to fall to yet another record low.

Investor services such as Moody’s continue to downgrade the country’s already junk-level credit ratings. Credit card spending quietly leapt 112 per cent in the second quarter, underscoring the growing desperation. And analysts expect Turkey’s economic growth to slow sharply to about 1 per cent by the year’s end, due in part to a possible recession in Europe.

The day after Sik’s remark, the AKP filed a suit against him, seeking 100,000 liras in damages for his attack on the party’s “respectability”. That same day, in something of a surprise, Korkmaz Karaca, a member of Mr Erdogan’s economic policy council named in the new Peker allegations, resigned of all his duties.

The first AKP figure felled by Peker’s online assault, Mr Karaca said he had never taken any bribes but that the online “lynching” spurred by Peker’s tweets posed a threat to his health. Two days later, on September 1, the second AKP domino fell as Mr Erdogan dismissed senior adviser Serkan Taranoglu, also implicated in Peker’s corruption accusations.

Turkey’s long-time leader has so far refrained from criticising former AKP ally Peker, who in turn has avoided implicating Mr Erdogan in any chicanery. But Mr Erdogan is rarely shy about going after journalists and political foes – and Sik could be seen as both. “He is a terrorist,” Turkey’s leader said on the weekend. “Let’s see how he will save himself.”

thenationalnews.com