WSJ Opinion: This Isn’t Your Grandfather’s Turkey

Erdo wsj

Erdo wsj

But Russia is not the only declining regional power changing Ankara’s calculations. Iran is reeling under economic sanctions. The Arab world is in free fall. Libya, Iraq and Syria are weak and war torn. Egypt no longer looks like a serious regional power. Add to this the drumbeat from Washington that the U.S. is reducing its Middle East presence, and one can see why Turkey is both tempted and threatened by the power vacuums opening up to its east and south.

Meanwhile, Ankara’s relationship with Europe has changed. Turkey’s door to European Union membership has been nailed shut. The Turks think Brussels will be permanently biased against Turkey, given Greek and Cypriot membership in the EU. Yet the EU has failed to develop into an effective regional actor and seems vulnerable to Turkish pressure on issues like refugees.

Ankara’s new world is no bed of roses. Russia remains a powerful presence that Turkey cannot dismiss. The Syrian civil war has been a disaster for Turkey, hurting its economy and bringing millions of desperate refugees across its borders. The EU is too weak and too divided to act effectively in the region, but Mr. Erdogan’s populist economic instincts have left his country vulnerable to foreign economic pressure and Turkey cannot afford to take on the European bloc.

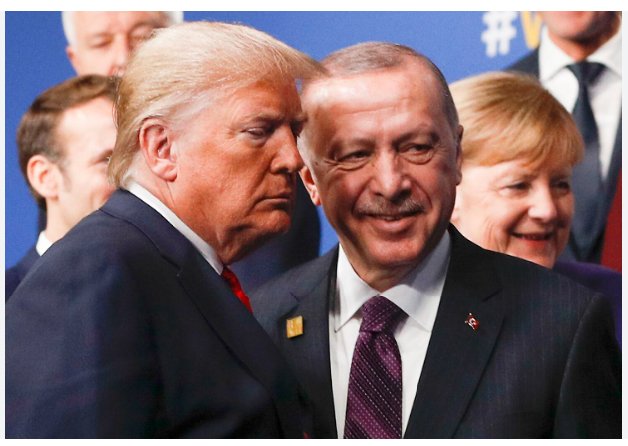

Despite their current estrangement, America and Turkey have common interests. Both countries would like to see peace and order in Libya, Syria and Iraq. Both would like Iran’s influence curbed. Both would like to limit Russian power in the Middle East, the Black Sea and the Caucasus. And across the vast expanse of Central Asia, both Ankara and Washington would like to see countries like Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan resist Russian and Chinese attempts to fold them into revived imperial systems.

Whatever happens to Mr. Erdogan and the Islamist movement he leads, Turkey will continue to become more modern and, let us hope, more democratic. But it will not necessarily become more Western. Ankara’s foreign policy will continue to become more independent and less predictable. If Washington expects Turkey to behave like the Netherlands, Norway or Spain, the relationship will frustrate both parties. But if the White House can start to think about Turkey the way it thinks about partners like Vietnam and India, policy makers will be able both to appreciate Ankara’s real geopolitical value and to manage more deftly the tensions that will inevitably appear.

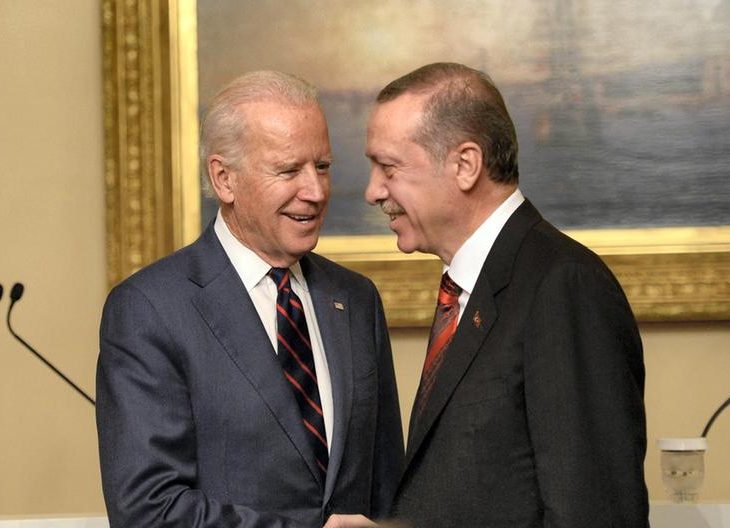

Mr. Biden’s job in his meeting with Mr. Erdogan isn’t to rescue the old U.S.-Turkish alliance, but to lay the foundation for a new one.

WSJ by Walter Russel Mead